Jim Johnson was backing out of his driveway as I pulled up. He stopped and beckoned me from his Dodge Ram, so I parked my VW and got in. "Where are you going?"

He handed me a sheet of paper and grumbled, "Janice left this list on the kitchen table. Keep me company."

Why not, I thought. I looked at the list. "The first item is, 'Drop Marie's purse off at JB's.'"

"Marie is Janice's friend. JB's is where she works. She must have left her purse at our house." He motioned with his head, "I brought it along."

In a few minutes we were at JB's Pub. I ran in with the purse, told the barkeep to give it to Marie and ran out. Jim gave me a wink. "Next "Pick up at One-Hour."

"That must be for our bedding. The cleaners is a couple blocks down."

Jim pulled in the parking lot and handed me twenty bucks. I walked in, asked the clerk for Johnson's stuff. I gave her the money, got the change and a bundle. Climbing back into the truck I announced, "Two down and two to go."

"Item number three, 'Can of Drano.'" He made an U-turn, made a right on Smith Rd., and pulled up to the Short Stop

This time he ran in leaving the engine running. When he returned he tossed the sack of Drano to me. "She probably thinks I'll forget to do this. But we"ll show her, right?"

"We?" I thought. I was just visiting. "Last item. Carnation. Why the flower?"

"Got me. I don't question Janice." Then Jim pointed out the window. "We're in luck because the florist is right across the street."

With all items checked off we headed back. In the kitchen Mrs. Johnson greeted us with, "Do you know where my list is?"

Jim set the goods on the table. "I thought you left the list for me."

"I gave up on you to run errands," she said.

Jim grunted. "Well we took care of everything. Here's our laundry from One-Hour, and the Drano." He thrust the flowers at her. "And here's a half a dozen carnations."

"Oh, really," she sneered. "I don't know whose laundry this. I already have our bedding. It was our vacation photos from One-Hour Photo. And thanks for the flowers, but I need Carnation condensed milk for cooking."

"Oh," Jim said sheepishly.

"And Marie's purse," she asked.

"We're not totally incompetent. We dropped off Marie's purse at JB's."

Janice tapped her foot. "Would that be JB's Sewing Shop?"

Jim rolled his shoulders and studdered "I..."

At least it wasn't "we".

"No, you're not totally incompetent. You did get the Drano," I heard her say as I sneaked out the door. "Would you like some?"

– Ω –

[ Go to end ]

Poor Jim Johnson got tangled up with language — with a list of words. But they were not just ordinary words. They were special words that denoted particular objects and locations. They were names, and I don"t mean in the sense that his was now "mud."

Those names were supposed to be unique and special. They should have had precise meanings, because that is what names do — they designate and distinguish people, places and things from other people, places and things. But in Jim's case those words were not unique badges identifying specific things. They were overworked syllables idling on a sheet of paper, waiting for Mrs. Johnson to give them meaning.

I remember a headline in the University of Arizona paper that made me do a double-take. The Daily Wildcat proclaimed, "Crank named player of the week." Of course the story was not about some eccentric athlete, but rather Monika Crank, a terrific young basketball player on the women's Pac 10 team. Another headline in another local paper read "Jester won't seek mayor's position." At first I thought it meant some joker dropped out of the race; instead the reference was to a candidate named Douglas Jester. In another instance I saw the news banner, "Turkey Seeks Compromise." No, it was not a tom negotiating his Thanksgiving future; it was the mid-eastern country in diplomatic action.

This kind of confusion happens a lot to us because so many names come from the dictionary of common words and so many common words were once names. We buy Aim from Target and Whirlpool from Home Depot. Bush is a former-president (or two) and Kennedy is an airport. You can read the Times anytime in Times Square, or meet Jack in the john, drive your Plymouth to Plymouth, or drink Dr. Pepper with your reuben. A Whopper is a sandwich, they make diesels in Flint, and you should not put Jello in a thermos. What is a colt? Is it a gun, a horse, a car, or the name of a person? Who's on first?

Is it A1 Sauce

or

a highway?

[touch]

But Mrs. Johnson's list had syllables (or spoken letters) that were obviously names, like JB's. A label such as this should have had a singular meaning, because isn't that the reason Jack Black, or Judy Boody, or whoever the proprietor of that sewing shop was, chose that name? Let's face it — even syllables that are obviously names still can be feeble messengers of meaning.

If you lived in Alaska, what would you think if you heard someone say, "Yesterday we took A1 to our picnic?" Did that person take the interstate highway designated A1 to a state park, or did he simply pack some A1 brand steak sauce in a wicker basket? Or maybe A1 is the model of his Audi car.

So why did Jim Johnson misread that list of names his wife had penciled? The only string of alphabetic symbols he got right was for a drain cleaner. Why was that? Why were some names "strong," communicating their meaning concisely and precisely with no context, while others were "weak," needing the help of other words, a specific speaker, or some distinctive setting?

It seems names become weak because they have no allegiance. They jump from object to person, person to place, place to object. It is like a game of tag. Places are named after people, like Houston and St. Paul. Boats and airplanes get named after places like Maine and San Antonio, and after people like Andrea Doria and Queen Elizabeth. Place labels are used by people like Tennessee Williams and Joe Montana. People's names signify objects like Mickey Finn, Rube Goldberg, and Foster Brooks. And place names can be anything from Little Heaven to Hell.

Often names seem to come from nowhere and then they bounce around all over the place. Take the case of Nelly Bly, an old name first found in a Stephen Foster song from before the Civil War.

Nelly Bly! Nelly Bly! Bring de broom along,

We"ll sweep the kitchen clean, my dear, and hab a little song.

(ref)

Then, along came a young woman who wanted to be a newspaper reporter. Born in 1867, Elizabeth Jane Cochrane. As a young girl, she loved pink and so was known as Pink Cochrane. When her father died, her mother remarried and she became Pink Cochrane Seaman. After a rocky childhood, her dream to be a reporter came true when John Cockerill of the New York World newspaper hired the woman despite sexist traditions then.

She took the pseudonym Nellie Bly from that old song (Nelly was accidentally misspelled) and soon showed herself to be an able and ambitious reporter. To increase circulation, Cockerill had Bly pose as an insane indigent from Cuba. As "Nellie Brown" she was committed to Blackwell's Island, New York City"s notorious asylum. She could only take it for ten days, then wrote a haunting account of her frightening stay. The piece was a hit and her fame rose.

(touch to enlarge)

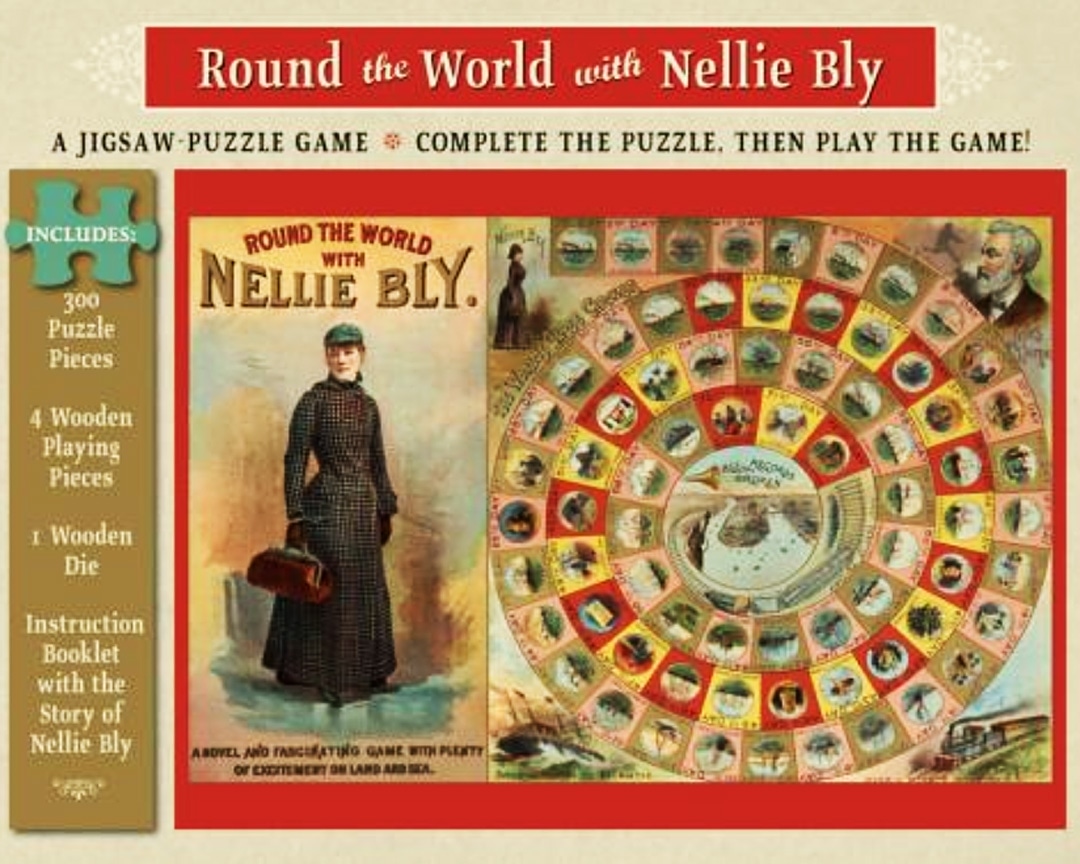

Next Cockerill wanted Bly to surpass the feat of the fictional Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days. In November of 1889, with much fanfare, Nellie began the journey. Publicity followed her the entire trip until she returned in just 72 days. The name of Nellie Bly was now world famous. Her name was given to a race horse, an amusement park, a fishing fly, and a train (that ended tragically). A game was created, "Around the World with Nellie Bly," and a song was written, "Globe Trotting with Nellie Bly". People named their children after her. There are several mines with her name as well as a creek in Oklahoma. And, for some obscure reason, there is even something called Nellie Bly Shale Formation. And so now in many places, Nelly Bly is now a weak name.

Similar tales can be told for other cultural lions, like Mae West, Babe Ruth, and Annie Oakley. These kinds of names get attached to things like floatation gear, baseball bats, rifles and any number of pets and places. There are ten Babe Ruth and two Annie Oakley Parks around the country and a Mae West Lake in Alaska. In each case we will find the name taking on additional chores other than just identifying a person. Soon the name becomes weaker and needs the crutches of context. In a tobacco store, the humorous question, "Do you have Prince Albert in a can?" would get a different answer than at Buckingham palace.

Do not confuse a name's meaning with a name's origin. In the current discussion when we ask about meaning, we want to know what idea or image the name communicates, not how it came to be. For example, if you call your dog Nellie Bly, that name means your dog. On the other hand, the name's origin is an inquiry into its prior meaning (a famous woman reporter called Nellie Bly), and perhaps the meaning before that (a name in an old song), and before that (Nellie comes from Eleanor meaning "shining light" while Bly is an Old English word meaning "high" or "tall") — and, like peeling an onion, the process can be continued until tears come to the eyes.

What do you think of when you hear about the Kennedy Center for the Arts? Probably you visualize the beautiful white marble structure bearing the name, or you recall some operatic performance you saw there, or maybe you just think of people in tuxedos and evening gowns. Most probably, the image of John Fitzgerald Kennedy does not come to mind.

Knowing that the Center got its name in memory of the assassinated president does not contribute to knowing what that location is. But if it is name origin you seek, you may be interested in knowing that the meaning of Fitzgerald is "bastard of Gerald" and "Kennedy" comes from the Gaelic for someone with an ugly or misshapen head. Knowing this origin does not allow you to better understand the edifice in Washington. Can you imagine going to the John, Bastard of Gerald, Ugly Head Center for the Arts?

Advertisement

More often than not, the origin of a name has little to do with the current meaning of a name. As far as we are concerned, a name means what it refers to, right? If only we could be sure what a name refers to. If it is a weak name, we cannot always know.

Consider the splendid cognomen Jefferson. What does that once presidential name mean? Is it labeling a person, a county, a street, or a nickel? In other words, because it is a weak name we need context to prop it up, to give it meaning. Consider: "I went to Jefferson." Not really informative until you add "…because he always has the answer" or "…then turned left onto Washington" or "…to study recreational brain surgery."

There once was an Ottawa chief who roamed the Northwest Territory in the 18th century. Born in 1720, this warrior was a principal in the French and Indian Wars, rallied a confederation of tribes, led a siege against the fort at Detroit in 1763, brutalized Indians and settlers alike, and was finally murdered near St. Louis in 1769. That brave and stout native gave birth to the most pervasive Indian name in America. Not only are there now nine cities and dozens of parks, streams, bays and schools named after that historic character, but from 1926 to 2010 there were millions of automobiles produced in the U.S., some either still cruising down some highway or rusting in junk yards somewhere, sporting that Indian's name, Pontiac. Fortunately his name was not Ossawinnamakee (check it out in Google search.)

Smith, being the most common surname in the United States, is naturally the weakest. One percent of all U. S. citizens are Smiths (more, counting motel guest aliases). Add the first name Jim and the label remains weak as evidenced by The Jim Smith Society with about 2,000 members nationally. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (certainly not a weak name) remarked about one fellow, "Fate tried to conceal him by naming him Smith."

Smith is not well represented on marquees. Noted personalities are one fourth as likely to have that name as unnoted people. The same is true of other popular surnames such as Williams, Jones and Brown. When fame comes they often get shed like a cheap coat.

Whoopi Goldberg

Take the case of Johnson. The once popular movie star Ava Gardner was formerly Lucy Johnson. Years ago a Caryn Johnson felt her name did not give her distinction as a comedian and entertainer, so she changed it to Whoopi Goldberg. Even a stronger first name such as Merle isn"t enough to prop up a Johnson, so thought the actor who became Troy Donahue. I guess if you want to make a name for yourself, you have to make a name for yourself.

But a weak name can be of some use. During World War II when the Allies were preparing to invade Sicily, they needed to convince the Nazis that the main assault would be upon the island of Sardinia. They devised Operation Mincemeat, a secret plan to have the enemy discover a dead body in an English uniform on the beaches of Spain carrying contrived documents alluding to a Sardinian invasion. British Intelligence obtained the corpse of a 34 year old Londoner named Glyndwr Michael who had committed suicide. Letters from a girl friend, receipts and personal effects as well as secret documents were fabricated. But what to call this "man who never was."

They decided to use the most common name in the British military service to make it difficult to trace. And so, on April 19, 1943, the body of Acting Major William Martin, dressed in a Royal Marine uniform, was loaded aboard the submarine HMS Seraph, and deposited off the Spanish coast near Huelva as if a victim of a plane crash. As planned, that "nobody" called William Martin was found. The Nazis took the bait and fortified Sardinia at the expense of Sicily where, in July, the Allies successfully landed.

Object names and place names can also be weak, particularly if they use common words like colt, sunshine, or total. Is "tiger" an animal, a sports team member, a computer program, a transport company, or a superb golfer? Pompous and lofty words, like "ace," "grand," and "quality" are so overused that they too invariably produce weak names. Such words almost always need to be accompanied by another word to provide clarity and recognition as with Quality Inn or Quality Dairy. (They should have called it Quantity Dairy, don"t you think?)

The words Hillary Rodham Clinton convey near perfect meaning for most Americans not in a coma. Each piece might be weak by itself, but together they communicate well. We find that complete and full names, like John Quincy Adams and University of Southern California, carry their meanings intrinsically and need little if any contextual help. In general, the longer the name, the stronger the name.

So why do some names have such precise meaning? Why is the meaning of Hank Aaron more certain than that of Hank Albert. In other words, what makes one strong, the other weak? As it turns out, there are two qualities that differentiate strong and weak names.

You might have figured out that renown is one of the traits of a strong name. It is almost too obvious; people must be familiar with a name to know its meaning, just like any word. Fame for a person, place or thing puts muscle into his/her/its name. We know Hank Aaron as one of baseball's all-time great players. Most of us do not know Hank Albert because he is an unremarkable guy — except to his wife, of course.

With the help of Hollywood, Ian Fleming could not help making a weak name into a strong one when his first spy novel Casino Royale became a success. He discovered the dull name for his hero on his coffee table, on a book about birds by an ornithologist name James Bond. Now the name is licensed to kill. Clearly, renown is a prerequisite for a strong name.

Benedict Arnold is a classic strong name. (Benedict is from the Latin benedicite meaning something like "bless you" and Arnold derives from a village in Nottinghamshire denoting a place ruled by eagles.) Every American knows these syllables to be synonymous with traitor, and nary a namesake is to be found in the country. The name's contemptible connotations make it a degrading moniker, an obvious insult. Its meaning is manifest, its independence from context unmatched. It is such a robust name we will be referring to it often in this essay. But why?

Benedict Arnold

Who was this scoundrel, this vile devil who betrayed his country, this Benedict Arnold? Those who knew him called him brave, strong-willed and patriotic. He fought in the French and Indian War, later prospered as a merchant, and had even sailed his own ships to the West Indies and Canada. During the Revolutionary War he was a colonel in the Continental Army and led American troops gallantly in many engagements with the British, suffering several wounds.

Then while commanding in Philadelphia, Benedict began to live a high life, spending money, misusing army property, and entertaining loyalists. He even married one, nineteen year-old Margaret Shippen. Embittered because he felt unappreciated by the Congress, he took a British bribe of 20,000 pounds to accept the West Point Command and convey information about its defenses. His act of collusion was found out, but he managed to escape to England where, too, he got no respect. His treason was not a decisive act, yet in a news-starved country it was big news. So Benedict Arnold got a lot of press.

However, renown does not guarantee a strong name. John Walker is a classic weak name, the union of two even weaker names, both prosaic to the point of boredom. John is not only a common, unimaginative first name in today's world, it has several low meanings. Walker is among the top 25 most common names in the U.S. It derives from an early English occupation common in the weaving industry where raw cloth from the loom was cleaned and scoured by men trampling on it. There are hundreds of people who have answered to the combination of these two handles (including the inventor of friction matches, and the New Zealander who first ran the mile in less than 3 minutes 50 seconds) and for most of us, its utterance stirs no emotions, evokes no images, and means little without the help of some context.

Yet a man with that very ordinary name committed treasonous acts far beyond Colonel Arnold. Arrested in 1985, this U.S. Navy employee had furnished the Soviets countless secret messages since 1968, and not for glory or out of a sense of betrayal, but merely for money. This man labeled John Walker was incomparably more villainous than that early fallen patriot whose crime was brief and came to nothing.

But even the magnitude of John Walker's misdeed was not enough to invigorate that anemic name. Where notoriety gave strength to Benedict Arnold's name, it did nothing for John Walker's. Not even a second John Walker in the employ of the Taliban in Afghanistan could give iron to this name. This suggests something else besides renown contributes to a name's strength.

It is a rarity. Like common words, a name that labels many things will be less precise in meaning, hence weaker. Think about it. Without a last name you might not know who Eva is, but how about Zsa Zsa? You know where Anaheim is, but Oakland could be anywhere. BurgerKing is a stronger name than McDonald's despite market share because this Scottish surname, meaning "son of the great chief" labels too many businesses, people and places, ee eye ee eye oh.

Strange as it may seem, our B. Arnold might have escaped eternal damnation had it not been for the tragedy that befell his older brother. It so happened that his wealthy parents, a drunken cooper named Benedict Arnold III and his wife Hannah, gave birth to their first son in 1738. Like his father and grandfather and great grandfather, the newborn was christened with the distinguished Rhode Island family name and became Benedict Arnold IV. Unfortunately, he died less than a year later.

The next son, born on January 14, 1741, thus became the next heir to, and owner of, that noble cognomen to the fourth. And it was he, Benedict Arnold's younger brother (shall we call him Benedict Arnold IV II?), who lived to see the founding of a new country — because of his heroism and in spite of his own late treachery.

The irony is that had the original Benedict Arnold IV lived, his infamous younger brother might have been given a more common name, and the traitor known perhaps as George Arnold, like the modern traitor John Walker, may have more easily faded into the trivia of history.

So rarity is necessary for the strength of a name. However, the reverse is not true. Rare names are not all strong. Nathaniel Brickman, for example, is rare enough, but it could be the name of a person or a pot pie. Fawn Creek, loveable though it may be, might name a rivulet, a community of cul de sacs, or a line of women's bras? No-Go-Pic is a unique name for some really cool stuff, but it too has no meaning since I just made it up.

Advertisement

We have all heard of the great Norse god of thunder, Thor, whose name became the root for the word Thursday. That bold syllable has renown but it is still a weak name because it gets used for labeling rockets, mountains, and Great Danes.

Now consider Thor's unfortunate kinsman, Berserk. What a marvelously rare name. This legendary Norse hero of the 8th century, so named for the bear skin he wore into battle, had 12 sons whose violence terrified the land and were known as Berserkers. The name was given to any wild warrior. Subsequently, it became an adjective to mean wildly crazy. Now, unlike Thor, Berserk is a weak name because it has virtually no namesakes at all, probably not even a wrestler or a radio disc jockey.

When I speak of a name being strong or weak, I am referring to its strength universally, i.e., across our North American, English-speaking culture. A universally strong name, like John Dillinger, may be weak in the Dillinger extended family. Likewise, a universally weak name can be strong locally, in a family, neighborhood, region, or organization. For example, the name Toledo Mud Hens has strong meaning to local fans. Yet, few people outside of Ohio would know that this name refers to a Triple-A baseball team. Not even Corporal Klinger of the TV series M.A.S.H could give that city team the notoriety of, say, the New York Yankees to make it comparably strong around the country.

An unfortunate lad with a universally anemic name was in law school at about the time of the Watergate scandal. TV and headlines gave new meaning to his name — President Nixon's legal advisor. For other John Deans in the world, the name had become locally weaker as it became nationally stronger.

Our law student had to endure fellow students pointing and saying "See that guy? His name is actually John Dean!" Using his middle name Edwin did not help to distinguish him from John W. Dean III. Whenever he would introduce himself, people would say things like, "I thought you were in Washington," or, "What are you doing out of jail?" Then when he was about to become a lawyer, he saw a headlines that read, "JOHN DEAN DISBARRED."

That is when he decided to change his name to Natty Bumppo after an Indian scout in James Fennimore Cooper's The Leatherstocking Tales. Because Natty Bumppo is not well known, it is weak universally even though it is rare. But to those who knew the former John Dean personally by his new name, it had unmistakable meaning and became locally strong.

Countless similar experiences occur everywhere, and the funnier ones get reported and retold in the media. Many years ago, for example, there was a man with the rare name of Woodruff Woodpecker. It was a strong name locally because everyone in town knew exactly who was referred to by the cognomen Woody Woodpecker. One day, however, he saw the local strength of that name sapped when the animator, Walter Lanz, popularized the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker. Now it is a universally strong name.

So what is the point of all this?

These observations suggest a general principle governing names as follows: renown and rarity produce a strong name. I call this the Smithski Principle, using the weak name Smith made rare with the common suffix -ski, an apt title for this extraordinarily insightful postulate.

These two qualities of a strong name, renown and rarity, can both be measured along a continuum, the renown value, a scale going from a low of "totally unknown" to a high of "world famous," and the rarity value spanning a scale from "utterly common" to "how do you spell that?"

So, for example, along the Renown Scale, a name such as Richard Nixon or Niagara Falls would have a high renown value while Philo T. Farnsworth or Laingsburg would have a low value. Likewise, along the Rarity Scale, a name such as John Smith or Avis would have a low rarity value while Gunning Bedford or Ishpeming would get a high value.

The combination of these two measures, Renown and Rarity, yields a coefficient called the Smithski Factor (the mathematics behind the coefficient will be left to some grad student looking for a thesis.) The following table shows examples of names at each extreme combination of these factors.

Name is |

Rare |

Common |

Renowned |

Strong Names People: John Dillinger Place: Alcatraz Product: Preparation H |

People: Adam Smith Place: New York Product: Avis |

Obscure |

People: Wilbert Fangman Place: Anamo Bay Product: Aunt Nellie's Beets |

Weak Names People: Tom Miller Place: Oak Street Product: Premium |

A Smithski Factor near zero means the name is so ambiguous that it needs a lot of context to convey meaning. For example, the ubiquitous name Johnson has a low Smithski Factor indicating it is a weak name. On the other hand, Magic Johnson probably has a very high Smithski Factor because it is a well known name (at least it used to be) and is unique as far as I know.

You might think brand names like Xerox or Kleenex are always strong names. Yet if you were to ask various working people if they have a Xerox in their office most would say yes even though the copier was made by Toshiba or Canon. Ask them for a Kleenex and you might get a Puffs. Because of careless language, and in spite of trademark laws, both of these names are now weak. They have come to mean more than their original proprietary referent. In other words, they have become generic names, or common words called eponyms. Other examples of once strong names becoming anemic eponyms include diesel, aspirin, thermos and bikini.

You might think that if two names refer to the same thing the longer name would be the stronger name. For example, we might agree that New York City is stronger than just New York, that James Earl Jones is stronger than James Jones (click on this link as proof) which is stronger than Jones, and that 5th Avenue is more precise than 5th alone.

But sometimes shorter names communicate better, as we see with Jimmy Carter vs. James Earl Carter, IBM vs. International Business Machines, and Fannie Mae vs. Federal National Mortgage Association. So even though longer names may be rarer, they may also be less known, and it takes both rarity and renown to make a strong name. (A friend has a traffic accident and says to you, "When AAA dropped me I joined AA." Get the message?)

Advertisement

If you think about it, you will realize that most strong names, i.e. those with a high Smithski Factor, are names associated with unpleasant things, names like Three Mile Island, Drano and Dracula. And conversely most weak names, those with low Smithski, are appealing in some way — names like Eagle, Total, and Franklin.

It should be no wonder that hardly anyone names her kid Judas or Edsel, or his dog Cujo or Rabies. We see no places labeled Puke Park or Salmonella Street. Have you noticed that we have several towns named Memphis and Troy but none named Sodom or Gomorrah? Are you surprised that there is a Prince Albert city, national park, sound, and brand of tobacco, but nothing comparable for Jack the Ripper? Is it not curious that the most common dog name is Lady and not Bitch? Did you know that Bertha has not been a popular girl's name since the gigantic gun called "Big Bertha" appeared in World War I?

It is true, by and large, that stained names are rare. And the greater the notoriety of a name, the more rarity it achieves. Look at the marvelous name Titanic, from the Greek mythical gods known as Titans (still an untarnished label.) Since that ship went down the only namesake anywhere is a movie about the ship and it surely increased Titanic's notoriety and ensured its rarity. After World War II most Germans with the surname Hitler changed it, pushing those syllables toward a rarity that matched its renown. When a cult called Heaven's Gate committed mass suicide and consumed the headlines in 1997, several namesake social groups and churches renamed themselves.

In contrast, look what happens to the names of our heroes, our hallowed grounds and the symbols of our ideals. These names stand high on the leg of renown through deeds and daring, courage and character — names like Jefferson, Enterprise, and Alamo. But then, over time, worshipers proceed to give away those cherished names to other people, ordinary places, and mundane things, essentially chopping out that other leg of a strong name – rarity.

Look what happened to the name Lincoln after 1865. Before Abe's martyrdom these syllables referred to only one thing for most Americans, a controversial president. Afterwards, over the years, it was attached to a dozen cities, a couple of mountains, and several lakes. It became a tunnel, a penny, and a car. "Abe Lincoln" is used in corporate and restaurant names, and as brand names for booze and bricks. But in the Old South, where the man was detested for so long, the name of Lincoln had a clear and singular meaning: the devil who became president.

George Washington

The most dramatic example of a cherished name becoming weak is that of George Washington. That full name is attached to a bridge, an aircraft carrier, several colleges and fellowship programs, a town, and hundreds of people. There is even a town named George in the state of Washington. (Check out U.S. Presidents.)

The single name Washington has been given to a pie, a square, 33 counties, seven mountains, the seat of national government, a state, 43 cities and communities, numerous streets and 2,000 other places in the country. It is the 90th most common surname in the U. S. In 1952, Nat Washington from the State of Washington ran for Congress with the slogan, "Send Washington to Washington for Washington."

On the other hand, nothing is named after Benedict Arnold. And if anything is named Benedict or Arnold, it is not because of the infamous colonist. Considering Benedict alone, what probably comes to mind is Eggs Benedict. Yet it is only because the name is so rare today that it gives us this lonely association, even if for only a split second. In fact, this poached egg on buttered English muffin and topped with ham and hollandaise sauce is from the surname of a New York socialite, Samuel Benedict, who, after overdoing it at a party one night in 1894, ordered the concoction the next morning as a cure for a splitting headache.

Benedict is a family name in our culture but it has not been popular as a first name since the end of the Revolutionary War. As far as Arnold is concerned, it has always been weak, being popular as both a first and a last name. Together, though, these two names produce a synergy that will remain eternally strong in American culture.

Yes, there are exceptions to the Smithski Principle, like the strong and likable, yet rare, names of Liberace, Mt. Rushmore and The United Nations. Mother Teresa is also a strong name, although there was a Nashville coffeehouse that named a shellacked bun after the saintly woman. Following a letter of disapproval from her, the entrepreneur renamed the bun. I cannot imagine what this guy was thinking.

Likable names that stay strong are often brand names like Cheerios, EBay and Volkswagen that maintain some strength through the trademark laws. In fact, it is because of the Smithski Principle that we have such laws. But even here we have no way of knowing to what extent protected good names have been given to goldfish, boats, and bowling balls. I knew a coffee-colored dog named Sanka.

Likewise, there are exceptions with dour names that are not always strong because of some peculiar circumstance. The word "gore" is most often found in gruesome and tragic contexts. Yet " Gore" is also the first name of author Vidal and the last name of a politically active family in Tennessee.

The moniker "Red Devil" is the name of a cocktail, a brand of hand tools, numerous other commercial products and many sports teams. (On the other hand, the equivalent "Red Satan" is unheard of.) There used to be a pub chain called the Alcatraz Brewing Company cashing in on the prison motif. The restaurant featured campy names for its brews from Big House Red to Birdman Brown. (You don't suppose the name had a part in its demise, do you?)

Another blatant exception to the Smithski Principle is the cheerless name of Tombstone. To begin with, there is a town in Arizona with that name. A guess at its origin might involve something about gun fighters, the OK Corral, and slabs of engraved stone rising unevenly in a weedy cemetery.

The truth is in 1877, a prospector named Edward Schieffelin set out across the San Pedro Valley of Arizona to find his fortune. This quiet and determined man made camp at Fort Huachuca where soldiers and other miners watched him ride out each day into the hills looking for precious rocks often returning late at night. The soldiers warned him that the Apache warriors would get him, that the only rock he would find would be his tombstone. But when Schieffelin discovered rich veins of silver one day he remembered the warning and mockingly named his first claim "Tombstone". The area thrived and the new town nearby took its name from that site.

But over time that once strong name was sapped when 36 other geographical sites, numerous businesses within the city, and a nationally known pizza took the name. I guess the glory of the old west out-muscled the pall of death. Oddly enough, the pizza was named after the Tombstone Tap, a tavern across the street from a cemetery, where two brothers turned a house specialty into a booming business. Would you buy a Mausoleum Burger?

In spite of the exceptions, I believe the tendency is for strong, good names to become weak and less precise in meaning over time, while nearly all strong bad names stay strong and unambiguous. Recognizing this tendency, I have formulated an extension to the Smithski Principle.

It is based on the need of people to associate with the glory or charm of great people, historic places and nice things, and to distance themselves from the negative, hopeless and even mediocre parts of life. It holds that really unpopular names rarely or never get used again for anything and hence never have their meaning confused with anything else.

An excellent illustration of this notion is the name of Benedict Arnold. We have discussed its rare and notorious qualities at length here. And based upon this exemplar name, I call this phenomenon the Benedict Arnold Corollary to the Smithski Principle and state it as follows: Infamy is the only guarantee for a strong name.

The corollary is exemplified by names like Alzheimer and Chernobyl, both relatively rare before they were cursed by fate and propelled to odious renown. Hence, whenever a name becomes completely and utterly distasteful, it is said to have become a Benedict Arnold, that is, a strong and infamous name. This concept can be used in a sentence like this: "He had a good name until it turned Benedict Arnold."

I was tempted to call the corollary after Adolf Hitler, the premier example of its truth. But I recoiled with revulsion. Even if the name was appropriate I could not come to use it. It was not the Adolf, which means "noble wolf," that bothered me so much, although it too is stained. It was not even the two syllables "hitler," a German appellation meaning "supervisor of salt works," that bothered me. But together the full name of that historic monster was just too repugnant. There is no question that its offensiveness surpasses even camp in vulgarity.

This most demonic and distasteful name truly demonstrates the validity of the corollary to the Smithski Principle. Nothing will share that awful Nazi name so as to weaken it, not even the concept that it epitomizes, the concept I chose instead to call Benedict Arnold.

(See also Common Surnames in the U.S.)

|

Other Pages in Names Galore | |

|

Famous Cowboy Names Sports Team Names Other Name Lists

|

Name Generators Naming Fun Stories about Names

|