One Columbus Day, while we walked our dogs together down Delaware Avenue, Jim Johnson asked me where I was from.

"I'm a Michigander. My wife and I both are," I replied.

"That would make your wife a Michigoose," he said as Moscow, his Russian wolfhound, pulled at his leash

"I suppose." I yanked on Yonkers, my American street dog straining to sniff a fire hydrant. "How about you?"

"I'm a Hoosier."

We stopped at Nevada Street waiting for the light to change. "Oh, so you're from the State of Hoosey," I said.

"No! Indiana." When Jim Johnson saw me smile, he shook his head.

I gave a tug at Yonkers who was checking under Moscow's tail. "Indiana? Did they name the state after the Asian country south of China?"

Moscow growled at Yonkers. "Very funny," Jim said. "At least it wasn't named after a potato."

I was puzzled. "Michigan wasn't named after a potato."

"No, but wasn't Idaho?"

– Ω –

[ Go to end ]

We so often take names for granted, hardly realizing that if we do not make the effort to design them, they get created anyway by the mere use of language. This often happens with place names, like Little Rock, Grand Canyon and Main Street. But you would think that naming a state would be special, a significant item on the legislative agenda, a matter of great historical and cultural importance, not left to chance and the vagaries of language.

Yet one wonders how some of the states could possibly be named what they are. We find names based upon foreign rulers, Spanish impressions, native Indian tribes and even Indian phrases — a lot of Indian phrases. Doesn't it seem a little odd that the settlers who were not particularly fond of the natives, or impressed with their culture, would name their states using tribal vernacular? Fortunately we don't have a state named How.

West Virginia [touch]

It turns out that most states inherited their names from casual or spontaneous designations. Like camouflaged warriors outside the fort, those phrases inched forward unnoticed until they were inside the gate. Uninspired names gained uncontested authenticity and nostalgic affection. In other words, people grew used to the names and before long, changing them was more trouble than not.

Take West Virginia. The state was originally part of Virginia, named for the queen of England, Elizabeth I, or rather for the state of her maidenhead. On the other hand, its origin may have been from the Indian chief named Wingina who met the English settlers at Roanoke, whereupon the "virgin queen" origin was adopted later to cover up a diplomatic blunder. In any case, the western counties of "Old Dominion" had anti-slave sentiments, and when Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861 they seceded from Virginia.

At first these westsiders were called what they were, West Virginians. But then they began calling their new confederation Kanawha, an obscure word from the Connis Indian tribe meaning "place of the white rock." The word was also the name of a river, a mountain range, and the most populous county in the territory. Then in 1863, when the rebellious counties were about to be admitted to the Union, delegates gathered to choose a state name. Kanawha seemed to be an inside favorite, but after much debate the vote was West Virginia 30, Kanawha 9, Western Virginia 2, Allegheny 2, and Augusta 1.

Strange, isn't it? Here was a spirited people so distressed with their slave owning neighbors that they broke all ties with them. Yet they rejected the beautiful and popular native name of Kanawha in favor of one rooted in royalty, cloaked in a slave tradition, and associated with an enemy of the Union. Being on the winning side of the Civil War you would think that these Virginians from the west would at least have forced their vanquished neighbors to change their state name to East Virginia for parity sake. Even better, if the Kanawhans liked the name Virginia so much they should have appropriated the name exclusively and made their rebel brothers take a new state name, like Jeffersona or Leeland or even North North Carolina.

So why is there a North and South Carolina? Or North and South Dakota? Why would not the residents of either of the twin states prefer an original name? The answer for the Carolinas is that the history of the region overpowered other considerations for naming the two states. After Sir Walter Raleigh failed to set up a settlement in this area in the 1580s, Charles I of Great Britain gave the task to Sir Robert Heath his attorney general. In 1629, Heath's patent from the king declared "we doe erect & incorporate them into a province & name the same Carolina or the province of Carolina, & the foresaid Isles the Carolarns Islands & soe we will that in all times hereafter they shall be named." Heath chose to honor his king in Latin, which is why we don't have a North Charlesina and a South Charlesina. Other than that, Heath had little to do with the Carolinas.

Virginia, North Carolina,

South Carolina, Georgia, circa 1763

Settlers began arriving in such large numbers that by 1689 the government of the north Carolina region had to be administered by a separate deputy appointed by the Governor of Carolina. By 1729, the north region had its own governor. Disagreements and troubles pushed the Lord Proprietors further apart and what was once known as Province of Carolina now had become "north Carolina" and "south Carolina". By the time the War of Independence was won by the home team the respective names were imbedded in the culture and tradition of the region, and the colonies of "North" Carolina and "South" Carolina for all practical purposes became the states of "Northcarolina" and "Southcarolina."

There is a curiosity in this history. The north Carolina region had a nickname of Old North State in colonial days. Had this label become more accepted and widespread we might have had, along with all the "New" states, one called Old North in the south.

The Dakota state names, on the other hand, were a bit more premeditated. Before there were states in the vast northern region beyond the Great Lakes, the natives called their territory "dakota," from the Sioux language meaning "many in one" referring to the loose confederation of tribes located there. By the end of the 18th century, the non-natives acquired most of that land piecemeal from Britain and France and took the name as well.

In preparation of statehood, the territory was divided, and in 1889 the two state candidates competed for the venerable name of Dakota. The Solomon compromise was for both to use the name, but each with a compass prefix. Now, like the Carolinians, the people of Dakota must share not only the last part of their state name with each other but also the first part with a distant state. There have been recent attempts in North Dakota, in defiance of the original agreement, to change the state's name to simply Dakota. One wonders if this should happen, how would the South Dakotans retaliate; perhaps by renaming their state to Classic Dakota or DakotaPlus?

By and large the first visitors to the new world lacked imagination in naming places. One of their favorite no-brainer methods was to take an old European name and put the word "new" in front of it. Up and down the coast of both American continents the Europeans founded such sites as New Amsterdam, New Spain, New Hampshire, New Brunswick, New Jersey, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and dozens of other "new" places. You would think that since these brave souls had powerful incentives to leave their homelands — including religious persecution, taxation, tyranny, and famine — they would apply fresh, idyllic names to their new homeland, names like Graceland, Heaven's Gate and Healthy Choice.

In fact, colonists had little to do with most original place names in the new land. It was the explorers and privateers, the king's men, who decades or centuries earlier, blithely and patriotically went around naming places after their homeland and sovereigns. For example, Henry Hudson, operating under the auspices of the Dutch East India Company gave the region around Hudson River (dubbed by guess who?) the name New Netherlands in the early 17th century. The city at the mouth of the river was called New Amsterdam. The less than loyal Dutch colonists that followed simply settled the land that already had been named. Then shortly afterwards, when James, Duke of York, led the British in taking control of the region, he cleverly renamed it after his old dominion and the place became New York — city, colony, and subsequently state. Well at least the city's name is easier to say than New Amsterdam, New Amsterdam.

The name New Mexico may seem particularly puzzling, even to someone moderately familiar with the history of the southwest. As victors in the boundary war of 1848 with Mexico, the U.S. claimed all of the land from the Oregon Territory in the north to the Gila River in the south. Then in 1853, under pressure from railroad interests, President Pierce had James Gadsden negotiate the purchase of an additional parcel south of the Gila River for $10 million. With American troops in Mexico City, the Mexicans thought it was an offer they could not refuse. With this inglorious vignette of "manifest destiny," it might seem, on one hand, outrageous that one country would steal land from another and then flaunt the prize by naming part of it after the victim. On the other hand, one might wonder why the American residents of the purloined property would prefer to be called "new" Mexicans. Such naming makes as much sense as naming Alaska New Russia.

The truth is that history had indelibly etched that name, New Mexico, into the land long before the dislocated Europeans got there. The seeds began in the 15th century far to the south with the great Aztec civilization that called itself Mexica. By 1519, the Spanish under Herman Cortes redeveloped the region as New Spain — but the native name would not die because, along with native resistance, the Spanish found "Mexico" easier to say than "Tenochtitlán", their rebuilt central city. In 1530, the crazy governor of the territory, Nuño de Guzmán, launched expeditions to the north to find gold and the fabled Seven Cities. Instead he found only beautiful mountains and expansive deserts.

Over the next decades, as settlements arose along the Rio Grande, this "land of enchantment" became known to the natives as Nuevo Mejico. By the time of the war with the U.S. even the gringos were calling the area New Mexico. As years passed the two words "new mexico" became a single designation that took the color of the land and its people. The name had become the majestic scenery, the sagebrush and mesquite, the brown people dressed in skins and beads, adobe huts, blue sky, and hot winds. When statehood came in January, 1912, there was no other name for it except that in-grown phrase, "noo-mek'-see-coe."

Many state names came from lousy translations. In 1682, when two Frenchmen, Robert De La Salle and Henri De Tonti, came upon the Quapaw tribe, they were unable to communicate with the people. They discovered a captive of the Illinois tribe being held there and, in the Algonkian language that they were familiar with, asked him what tribe his captors were. The captive responded that these people were from the "akansa" tribe which was his way of saying the "downstream people." The French plural adds an "s" and the tribe became the "Akansas." At some point an "r" slipped in and eventually the nearby waterway was named the la rivière des Arkansas and the region, then the state, was named after the river. Thus Arkansas narrowly missed being named Quapaw.

There is another origin story that attributes the name Arkansas to a French Jesuit, Jacques Marquette, who recorded the "oo-ka-na-sa" tribe on his map in 1673 as "Arkansea." You might think that one or the other of these accounts might somehow explain the origin of the Sunflower State's name. In fact, they may since the name for Topeka's state is taken from a Sioux tribe called the KaNze which means "the southwind people," probably the same folks as the "downstream people."

So why is it that Arkansas is not pronounced the same way as Kansas? Blame it on those English-speaking interlopers who mangled the French pronunciation and came up with something that sounded like "Arkansaw" which became the spelling used in the Act that created the territory. Later in 1881, after a boisterous and heated debate, the state legislature made that pronunciation official. Meanwhile, not far away, the pioneering people of Kansas pronounced it like they saw it.

One western state name came from the far east Indians — that is to say as far east as Pennsylvania where the Lenni-Lenape Indians lived along the Susquehanna river. Known to us as the Delaware (after the river that was named for Lord De La Warr, first governor of Virginia), this tribe called its village "on the great plains" which was something like "meche weamiing" in the Algonquian tongue. When whites took up residence there, they butchered the syllables and before long the site was called Wyoming. Unfortunately, on July 3, 1778, the inhabitants were attacked and massacred by a combined force of British soldiers, Tories sympathizers and Iroquois Indians in the Battle of Wyoming.

The name Wyoming would have receded into the trivia of history had it not been for a Scottish poet, Thomas Campbell, who in 1809 published an account of that tragedy in his poem, Gertrude of Wyoming. Soon dozens of cities and counties across the continent were adopting the tragic name. And when the Union Pacific railroad brought settlers to the immense plains of the southern Dakota Territory in the 1870s statehood was inevitable. In 1890, Ohio Congressman J. M. Ashley liked Campbell's poem and suggested that the mangled Algonquian phrase was most apt for the place... and so we have Wyoming, instead of South South Dakota.

Advertisement

Not all state names have such a nicely documented history. A few origins are quite speculative. For example, Arizona may have come from the Spanish arida zona (dry belt) or the Indian arizonac (small spring.) Some historians believe Oregon was named after the northern river that the French called the Ouragan, meaning "hurricane." Others believe that due to a mapmaker's error in the 1700s travelers to the west thought they were heading into territory named Ourigan, after a river. Or the name might be related to the oregano which grows in the southern part of the region. Likewise uncertain is Idaho which might have been from a Shoshone language term meaning "the sun comes from the mountains." Or it might be a Kiowa-Apache term referring to the Comanche. Or it could have been named after the county in the area which was named after a steamship launched on the Columbia River in 1860. Or it may simply have been a made-up name. But for sure it was not named after the potato.

In any case, the table "Source and Meaning of State Names" offers the prevailing consensus on the source and meaning of all the state names. By and large, the state names are distinct and handsome, bound in tradition and beloved by the new natives, excuse the expression. Even Texas &mash; which looks so much like Taxes &mash; has a place in many hearts, as well as Missouri &mash; which very nearly sounds like a state of gloom.

Looking at this list I could not help but wonder what states would be named if we had to start all over? When you look at the names we give commercial products, businesses, streets, and communities nowadays, you realize we would not be limited to just Indian words or the labels already owned by people or other places. The state legislatures could use jazzy expressions or pleasant but sterile phrases, or just invent words or misspell them. Based upon contemporary naming practices, I wonder if the 50 states would not have names more like those given on the map "States Renamed."

If any new territory is ever to be added to the Union, we need not worry about such silly names being applied because undoubtedly the new member will be named the same as the territory. For example, there might be a state of Puerto Rico, or Guam, or Manhattan, or even British Columbia (you never can tell.)

But what would we call the territory that currently is the District of Columbia if, as some propose, it be given statehood? Certainly not Washington. Maybe East Washington. Or perhaps Columbia. Nah, that would just arouse again all of those heated discussions about that nasty Genoan who only managed to pilot the first cruise ship to the Bahamas without even knowing it. How about Jeffersonia? Or Franklina, Lincolnia, Kennedia? Or my favorite, Johnsonia? Or maybe just plain Capitola? Write your congressman.

In Michigan, there have been periodic discussions about making the Upper Peninsula a separate state, mostly by those living in the U.P. (Yes, "yoo-pee" does sound a little off-color, but that is how that part of the state is referred to. On the other hand, the lower peninsula, the part shaped like a mitten, is never referred to as "el-pee.") The vast northern territory across the Straits of Mackinac was given to Michigan by the U. S. Congress in 1837 to make up for the piece of land lost to Ohio following the Toledo War of 1835.

U.P. ers, or Yoopers as they call themselves, are sometimes frustrated by the lack of respect from the down-staters. As an autonomous state, if the idea ever does comes to pass, you might guess that this pine wilderness would be named something like Uppia, Wolverine, North Michigan, or maybe even East Wisconsin. Well don't bother thinking about it — the Yoopers have already decided upon Superior as the name, presumably after the Great Lake on its northern shore and not upon any cultural comparisons.

If you live in Georgia you are a Georgian, if in Montana a Montanan. But what if you live in Massachusetts, what do we call you? Normally state names are the basis for labeling the residents. These labels are called demonyms. In general getting a demonym from a state name is usually accomplished by adding an ending such as "an" or just "n" if the word ends in "a." Sometimes adding "er" or "ite" is sufficient. For example, a resident of the Golden State is known as a Californian. One from the Empire State is a New Yorker. A person born in the Badger State is a Wisconsinite. Some demonyms get tricky, like Texan instead of Texasan, or Utahn where you might expect Utahan. Natives of the Great Lake State can be designated either as Michiganians or Michiganders — and no, the women are not referred to as Michigeese.

So what about those people from MA? There is no good suffix that fits the state, although Massachusettite, Massachusettsite and Massachusettan have been suggested. Most serious publications refer to the citizens of Massachusetts as the "citizens of Massachusetts." But the residents of the Bay State simply refer to themselves as Bay Staters. Yes, the state is also known as "Old Colony" but no one there calls himself an Old Colonist.

The only other curious case is with Connecticut. Attempts have been made to refer to the people there as Connecticuters and Connecticutites. Other mouthfuls proposed include Connecticotians by Cotton Mather in 1702, Connecticutensians by Samuel Peters in 1781, and Connectikooks by contemporary comics. In fact residents of the Nutmeg State are simply and officially known as Nutmeggers. Why?

|

State Demonyms — What do you call someone from the state of... | |

|

Alabama... an Alabamian or an Alabaman Alaska... an Alaskan Arizona... an Arizonian or an Arizonan Arkansas... an Arkansan or an Arkansawyer California... a Californian Colorado... a Coloradan Connecticut... a Connecticuter or a Nutmegger Delaware... a Delawarean Florida... a Floridian Georgia... a Georgian Hawaii... a Hawaiian or an Islander Idaho... an Idahoan Illinois... an Illinoisan Indiana... a Hoosier or an Indianian Iowa... an Iowan or a Hawkeye Kansas... a Kansan Kentucky... a Kentuckian Louisiana... a Louisianian Maryland... a Marylander or a Free-Stater Massachusetts... a Bay Stater or a Massachusettsan Maine... a Mainer or a Down Easter Michigan... a Michiganian or a Michigander Minnesota... a Minnesotan Mississippi... a Mississippian Missouri... a Missourian

|

Montana... a Montanan Nebraska... a Nebraskan Nevada... a Nevadan New Hampshire... a New Hampshirite or a Granite Stater New Jersey... a New Jerseyan or a New Jerseyite New Mexico... a New Mexican New York... a New Yorker North Carolina... a North Carolinian or a Tar Heel North Dakota... a North Dakotan Ohio… an Ohioan or a Buckeye Oklahoma... an Oklahoman or a Sooner Oregon... an Oregonian or an Oregoner Pennsylvania... a Pennsylvanian Rhode Island... a Rhode Islander South Carolina... a South Carolinian South Dakota... a South Dakotan Tennessee... a Tennessean or a Volunteer Texas... a Texan Utah... a Utahn or a Utahan Vermont... a Vermonter Virginia... a Virginian Washington... a Washingtonian West Virginia... a West Virginian Wisconsin... a Wisconsinite Wyoming... a Wyomingite

|

Hearsay has it that the early Connecticut peddlers tried to sell wooden nutmeg seeds in place of the real thing. Their shady image was popularized by writers like Thomas Chandler Haliburton with his fictional Yankee peddler, Sam Slick, who sold nutmegs made of wood. Scottish author Thomas Hamilton, following his tour of the U.S. in 1833, wrote that the peddlers "always had a large assortment of wooden nutmegs and stagnant barometers."

So all the Connecticut Yankees were derided as Nutmeggers. The fact is that the shell of a nutmeg is wooden and cannot be opened by just striking it like a walnut — it must be sawed. Knowing this, the natives had the good humor to make Nutmegger a label of respect. Can you imagine the people of Hawaii being called Pineapplers?

There seems to be no consensus about what to call a native of Indiana. Although "Hoosier" seems to be preferred by sports fans, "Indianan" gets a lot of official ink. Certainly it makes more sense than Hoosier, that Gaelic slur meaning "hill dweller." On the other hand, the word "Indianan" has an odd history, beginning as a short syllable and growing like an onion as it moved west.

Thousands of years ago an ancient tribe crossed the wide lowlands beyond the Sulaiman Mountains in Asia and came upon a great river which they called Indus (or Indi, probably a Greek word,) and settled that fertile valley and the lands beyond. For centuries the eastern cultures were forgotten by the West until Marco Polo, after a tour of the Far East, wrote about India (he added an "a" to Indi) from his jail cell in the late 13th century and told how it overflowed with jewels, gold, spices, and silk. For Christian Europeans, India (meaning all of the Orient including Cathay (China) and Cipangu (Japan)) was difficult to get to because you had to either sail around Africa or go through the infidels' backyard.

Cristoforo Colombo had a better idea — he would get to India the other way, west across the Atlantic Ocean. Sure enough, when he hit land he was met by a bunch of "Indians" (notice the added "n".) Unfortunately they were the wrong Indians. But it was too late and the name stuck.

Over the next several centuries, restless Europeans pushed their way onto the new continent (which was not called India) and chased the natives hither and yon, but mostly yon to a place called "the land of the Indians" just east of the Mississippi. But by 1816, after most of the Indians were pushed further yon, the territory was admitted to the union as, what else, Indiana (just add an "a") — and the people of the state were called Indianans (and another "n"). I wonder if these Indianans should ever settle elsewhere would the new place be called Indianana, and its new inhabitants Indiananans?

Advertisement

It turns out that state names have been fodder for city and town names, or "populated places" as the U. S. Geological Survey classifies them. There are 204 such places in the U. S. with cloned state names. The best known, of course, is the city New York. The most popular name, of course, is Washington with 27. There are several city/state doublets: New York, New York; Kansas City, Kansas; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and Florida City, Florida. All the other state-named communities are in differently named states. These cities and towns must surely cause the Post Office constant mix-ups with addresses like; Iowa, Louisiana; Texas, New York; Nevada, Iowa; Montana, Wisconsin; and Indiana, Pennsylvania, home town of the late movie star Jimmy Stewart. (I wonder if he ever thought of himself as a Hoosier.)

There are hundreds of towns and cities that use a state name with some other qualifier such as City, Ridge, Valley, Point, Beach or any of dozens of other modifiers. Among these are Wyoming Valley, Maine Prairie, and California Junction.

In 1847, the Michigan Legislature moved the state capital from Detroit to the new town they named Michigan, located in a wilderness where Chippewa Indians roamed and a few pioneers from New York had settled. That's right, the capital of Michigan once was Michigan — until 1848 when local leaders proposed that the name be changed. The new legislature took up the matter and debated the candidates that included such authentic Michigan syllables as LaFayette, LaSalle, Houghton, Aloda, Huron, and Cass. But personal sentiment and political power were more influential, and the winner was the hometown of those settlers from a town in New York which honored a late New York Supreme Court Judge, John Lansing, whose ancestors, the Lansinghs, came from Amsterdam where "ingh" meant "son of" and "lan" referred to a holder of land. Aptness is a subjective thing.

There are hundreds of examples where a suburb with no imagination takes the name of the neighboring urban area and adds some modifier, as exemplified by Miami Beach and Cleveland Heights. Sometimes this trend gets strangely twisted as with West Palm Beach which is vastly larger than its neighbor Palm Beach. There is no community named Daytona, yet there is a Daytona Beach, a Daytona Beach Shores and a South Daytona.

Often a second tier city will take a big city name and append a compass point to it; for example, West Palm Beach, South San Francisco, East St. Louis, North Miami. Sometimes that is not such a good idea, as a town once called East Detroit found out. Our story begins in the late 16th century when Antoine Laumet de la Mothe Cadillac arrived at New France, what is now the Great Lakes region of North America. He came upon a deep clear river which he dubbed ile détroit du Lac Érie, meaning the strait of Lake Erie. There he founded a settlement called Fort Ponchartrain du Détroit, naming it after the comte de Pontchartrain, Minister of Marine under France's King Louis XIV. A century later the British managed to slur the name into "Dee-Troyt." As this early community prospered another village northeast of it sprung up as a stage coach stop, and by 1897 it was known by the name of Halfway. By the 1920s the name Detroit brought to mind prosperity, automobiles and industrial might. So in 1929, the neighboring town of Halfway decided to reincorporate as the City of East Detroit.

But after World War II, the sirens of suburbia beckoned and within decades "white flight" soared. By the 1970s economic decline and urban decay had muddied the Motor City's moniker and brought to mind images of grimy factories, old buildings, neglected neighborhoods, and the appellation "Murder Capital of the World." By the 1990s East Detroiters felt embarrassed by the second half of their name and they wanted a change. It so happened that another adjacent town had inherited a French name too, Grosse Pointe, a prosperous suburb that enjoyed such a posh reputation that other neighboring communities became Grosse Pointe Shores, Grosse Pointe Farms, Grosse Pointe Park, and Grosse Pointe Woods. So in 1992, the East Detroit city council renamed the community Eastpointe. Legend has it that Detroit mayor Coleman Young wanted to retaliate by renaming the motor city to West Pointe.

In March 1825, in southern Michigan, surveyors were working near a grove of maple trees from which local Native Americans got maple syrup. Legend has it that at one point, when only two men were left in camp, two local tribesmen came upon them. Being upset by the whitemen's intrusion, they began to skirmish with them. After a brief struggle the locals ran away. It is said this brief encounter gave rise to the name of a nearby stream, Battle Creek, and then the town that grew around it. One board member of the Historical Society of Battle Creek said the incident was not really a battle, "it was more of a kerfuffle." In other words, the birth place of the Kellogg Company and the cereal industry might have been called Kerfuffle Creek.

In the late 19th century, the 8,000 people of North Tarrytown, New York, in need of revenues after a General Motors plant closed, looked for tourist dollars. It had one great attraction — it was the location of Rip Van Winkle's famous nap in Washington Irving's famous story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The town was the site of Washington Irving's grave and it already had a Sleepy Hollow Animal Hospital, Sleepy Hollow Bicycle Shop, and Sleepy Hollow High School. All North Tarrytown needed was a new town name to go with the folklore. After an early effort failed, the town officially became Sleepy Hollow in 1996. Twelve other communities in the country already had that name, but not the legend.

Oakland is a common name for a town. This popularity is remarkable since, oddly enough, there are no other "Tree-lands;" no Mapleland, Elmland, Chestnutland, Beechland, or Hickoryland — just Oakland. These other trees show up in names with other words, like Maple Glen, Elmwood, Cedar Crest, and Hickory Farms, but so does Oak. With almost a hundred Oaklands in the U.S. it's almost as if the first president of the United States had been George Oakland.

There would be a lot less confusion if every town in the country had a unique name. When you say "Miami" you should not have to add "Florida" or "Ohio." When someone calls you from Hot Springs, you should not have to guess from the accent if the caller is in Arkansas, Arizona, South Dakota or one of nine other states. These towns ought to be encouraged to adopt more imaginative names, like the people of Hot Springs, New Mexico did in 1950. That year a TV game show host Ralph Edwards promised to broadcast the tenth anniversary show from any town with the same name as the program. The residents of the New Mexico community answered the challenge and voted to change the town's name to Truth or Consequences.

Speaking of unique names, we must hold up Albuquerque as a great example. Or is it Alburquerque, with that extra "r"? The name originated in 1706 when the provisional governor of the territory, Don Francisco Cuervo y Valdéz, petitioned the Spanish government for permission to establish a villa. Valdez greased the request by proposing to name the place after the man responsible for approving his petition, Viceroy Fráncisco Fernandez de la Cueva, the Duke of Alburquerque. But what happened to the first "r"? Legend has it that a sign painter for the railroad omitted it because he did not have enough room on a station placard for the whole name. Some blame it on the city postmaster. Others claim the "r" just disappeared mysteriously over the ages. Strange how the ages left so many other letters unscathed.

Naming towns after people is not that common but it does happen on occasion. For example, in 1947 the new community of Island Trees in New York was about to become an icon of American suburbia with its affordable single-family homes within driving distance of urban employers. After the 1,000th family moved in an anonymous letter to the editor of a local paper suggested naming the community after the developer. An informal poll showed support for the idea, so the landlord announced the community would henceforth be known as Levittown after developer William Jaird Levitt. Lucky his name wasn't Down.

At about the same time, the towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk had hit bottom following a long economic decline. These two towns at the foot of the Pocono Mountains in Pennsylvania prospered during the 19th century mining boom. Once a Mecca of the touring rich, by 1950, the towns had only scores of quaint but tired buildings and the notoriety of the Molly Maguires executions in 1877. So in 1953, the towns decided to jointly jump start their communities.

Their efforts came to the attention of Patricia Thorpe, whose half Indian husband had died that year. Born in Oklahoma Territory in 1888, the man called Wa-Tho-Huk or "Bright Path" by his tribesmen had become one of America's greatest athletes. In spite of this, his native state rejected the idea of honoring Jim Thorpe. So Mrs. Thorpe negotiated with the spokesmen from the two Pennsylvania towns, and in 1954, they agreed to rename the amalgamated communities as Jim Thorpe in exchange for her husband's memorial and grave. Isn't it curious that this old town in the Quaker State — settled by German and Irish descendants, once known by the Indian phrase Mauch Chunk (meaning "mountain of the bear"), now named after an Oklahoman of Sac, Fox, Irish, and French blood, who was born near the town of Prague (in Oklahoma) and whose American alias (Thorpe) came from the old Danish word for "hamlet" — should advertise itself as "the Switzerland of America"?

Then there is that mythical small town of rural America. In the early 17th century, a secluded tribe of Indians lived near what is now Hartford, Connecticut. Over the years they seemed to have disappeared. Finding them became a joke. By the 18th century, New Englanders were using the tribe's name to describe any remote or small place. In 1846 the Daily National Pilot of Buffalo asked, "Where in the world is Podunk?" It turns out the mythical town does exist — in several places. There is a Podunk in New York, Connecticut, Vermont, and two in Michigan.

Of the more than 150,000 populated places in the U. S. Geological Survey database, most are not noteworthy, like Fairview, the most prevalent. Yet some town names are melodic and fun to say, names like Biloxi, Pensacola, Amarillo, and Tallahassee which exercise the mouth and coax one to repeat the name again and again. Others tickle the humorous humerus. The table here offers just a sampling.

|

Town Names That Seem Amusing |

Town Names No Longer Amusing |

Pennsylvania must surely qualify as the state with the most diverse collection of names for towns and cities. In addition to the two on my list, its atlas sports such populated places as Bird-in-Hand (named after a saloon), Broad Top City, California, Gwynedd, Intercourse, Nanty Glo, Punxsutawney, State College, and Yoe. But I guess such names are to be expected in a state named Pennsylvania.

The premiere oddity in town names seems to be a "cross roads" town in lower Michigan with no cross road. It began in 1841 when George Reeves took over a sawmill at the dam on Hell Creek, then acquired other land in the area. Soon a flour mill, a general store, some houses and a school were added. People began to ask Reeves what he was going to name the town. "I don't care," he replied. "Call it Hell if you want to." The name stuck... and efforts to change it officially to Reevesville or Reeves Mill never succeeded.

Yet Hell, Michigan is not a hellish place. It is just another small town of friendly people in a heavenly setting of majestic trees, rolling hills and babbling waters. Hell's most prominent business is the Dam Site Inn, a folksy tavern a few yards from the dam site. The residents accept the levity prompted by the town name — the easy humor about "a cold day in…," "going to…," and other such remarks — as tourist amusement. And, yes, it freezes over every year.

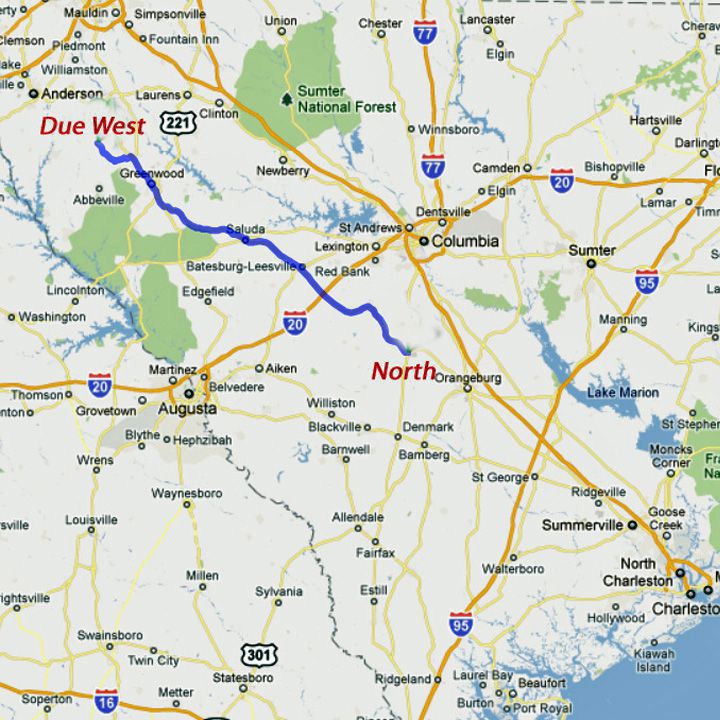

Directions from Due West

to North, South Carolina

A town called Hell is amusing because it is a small community with an odd name lost in a gargantuan culture. There are other names potentially just as amusing had they not been given to large and dynamic places. If you pretend you have never heard it before, you have to admit Oshkosh is a funny sounding name. Reading in Pennsylvania could be considered amusing also, as could South Bend in Indiana. But we do not grin or chuckle at these because the names long ago took the color of the cities. It is with this perspective I offer my other list of amusing town names in the table above, ones which a stranger might find entertaining but you might not.

Did you know that in South Carolina, to get to the town of North from the town of Due West, you have to go south east on US 178?

Before leaving the topic of populated places, we should note that scores of towns have numbers for names. I do not mean names with numbers in them, like Three Points, Arizona; Seven Hills, Ohio; Six Lakes, Michigan; or Twentynine Palms, California. Instead I am referring to towns like Forty Five, Tennessee; Seventy Six, Kentucky; and Hundred, West Virginia which was named after Henry "Old Hundred" Church, who died in 1860 at the age of 109. The most notable of these number names is Ninety Six, near Greenwood in South Carolina and pivotal to the several skirmishes of the Revolutionary War. The town was established as a trading post in 1730 and, although the place has its legends about an Indian princess and her colonist lover, it probably got its name because it happened to be 96 miles from the town of Keowee on the road from Charleston.

Residents of towns and cities also have demonyms. Although many city names lend themselves easily to the demonyms, like Detroiter, Tulsan or Bostonian, many do not; for example, Colorado Springer, Santa Barbarian, Shreveporter, Minneapolisinner, Corpus Christian, and Buffalonian. Indeed, jokesters have already given us, among others, Baton Rogue, L. Alien (from Los Angeles), Baltimoron, Tampon, Greensborrower and Omahog. But by and large, people in such towns as Helena, Santa Ana, Bowling Green, Fond Du Loc, and Long Beach don't bother with such endings. They just say "I'm from…" which unfortunately begs the reply, "That's a good place to be from."

Advertisement

So much for the states and all their "populated places." What about the country's name, that grand union of states? H. L. Mencken supposedly said that "the United States of America" is more a phrase than a name. My sentiments exactly. Five words seems quite unnecessary. The "the" is optional and probably so is the reference to the continent. The central words "united" and "states" are two gray words that separately incite no feelings, vision or spirit. And if the founding fathers wanted such a prosaically accurate name, should it not have been "The United States of North America"?

Now I confess I have a warm feeling toward my nation's name, just as I am sure most Canadians feel about theirs. But can you see the difference? One is a succinct, crisp name that they put in their national anthem, O Canada. The other is a verbose, dull statement which is never mentioned in The Star Spangled Banner.

How could it happen? What were our forefathers thinking? Was it a committee decision?

As usual the petty details of history conspired to force an unlikely name upon an unnamed entity. The pieces just came together: united, states, america... never with much premeditation. The oddest piece has to be the reference to the country's continent — America, North Wing. Why wasn't this land named Columbia after the man so celebrated for his new world discoveries? Why was it not called India? After all, the natives of the continent were called Indians. Why not plain old New World, or the once popular Terra Incognita?

To find out, let us start with that Genoese seaman, Don Cristoforo de Columbo, who commanded three ships on a daring expedition to China across the Atlantic Ocean, through the seaweed of the calm Sargasso Sea, and into the bajar mar (hence, Bahamas), or shallow waters. One of his lookouts, Rodrigo de Triana, on the forecastle of the caravel Pinta spotted a white sand cliff gleaming in the moonlight at 2 a.m. on the morning of October 12, 1492, and shouted "Tierra! Tierra!" It was not China, of course, merely the island Guanahani, or rather San Salvador as the aliens from the east dubbed it. But it was not this lowly crewman, Senor Triana, who got the erroneous credit for discovering a new continent, but rather his admiral.

Yet Columbus' dubious renown was not enough to get a continent or two named after him. It had something to do with a world map made in 1507 by a German professor, Martin Waldseemüller, which had placed the name America on the new land masses in the west. This map subsequently became the source for other mapmakers.

One theory has it that Martin Waldseemüller, the mapmaker, was crediting another Italian, Amerigo Vespucci, with the discovery of the new world. Senor Vespucci was a member of a 1499 expedition to the south Atlantic headed by Alonso de Ojeda, a despicable skipper who supposedly captured some English ships encroaching on his territory and slaughtered the crew. Amerigo sailed again in 1501 exploring the new southern coast, charting the southern skies, and naming many places including "little Venice," or Venezuela. Following a third trip Amerigo published Mundus Novus, his own accounts of the journey, supposedly the source of Professor Waldseemüller's map. Then in 1538 using Waldseemüller as a source Gerardus Mercator compounded the error on one of his famous maps by applying the name America (why not Vespucci?) to both new continents in the west.

In fact, Vespucci never set foot on the northern continent. One who did during this time was another Genoese seaman also looking for a westward passage to Cipango. Sailing from Bristol under the English flag, Giovanni Cabotto, the man we know as John Cabot, had reached present-day Nova Scotia and possibly even the St. Lawrence River in June of 1497. There is some speculation that one of his Bristol backers, Richard Amerike, was honored by Cabot as he labeled the new lands on his chart. Cabot took that chart on his second journey – but he and his crew were never heard from again. Could this be the English crew wiped out by that evil Spanish skipper, Ojeda? Could the English maps with the name Amerike on it have fallen into the hands of Vespucci? (For a thorough investigation into the origin of "America", see "The Naming of America" by Jonathan Cohen and Wikipedia's The Naming of America.)

In any case, according to these accounts, the southern continent should have been named Ameriga and the northern one Cabotia (pronounced either "ka-botch'-ya" or "kab-oh-tee'-a," take your pick). Oddly enough during the 15th century there were some Europeans proposing the name Columbana for the northern continent and Brasil for the southern.

The name "the United States of Cabotia" is certainly more historically correct than "the United States of America," (or even "the United States of Vespuccia"), but others could just as well stake a claim here. In the 6th century, it is likely that the Irish Monk Brendan of Clonfert crossed the Atlantic and probably landed somewhere on the continent. In 986 A.D., the Viking Bjarni, son of Heriulf, made it to what is now Newfoundland. In 1000 A.D., Leif Eriksson, aka Leif the Lucky, son of Eric the Red, using Bjarni's ship and a crew of 35, explored the coast of North America, possibly as far south as what is now Boston. Several years later, with 160 men, their wives and cattle, Thorfinn Karlsefni set out with three ships for Vinland. He spent four years on the North America continent. Sometime between 1003 and 1007 A.D., a child christened Snorri was born in the new settlement, the first non-Indian native American, or more appropriately, the first Snorrian. Then there is the Welsh prince, Madoc, who according to folklore, sailed to America in 1170 and perhaps intermarried with local Native Americans. In 1398, Prince Henry Sinclair of Scotland led an expedition to Nova Scotia. And in the 1480s, English fishermen from Bristol, in particular, one Hugh Elliot, claimed to have found a great fishing spot and the mythical island Brayssle (Brasil) west of Greenland.

Bjarnia

Bredana

Cabotia

Columbia

Elliotia

Ericssonia

Hojedaia

Karlsefnia

Leifia

Luckyleifia

Madocia

Mexica

Sinclairia

Snorria

Thorfinnia

Given this pre-Vespuccian sea traffic we can wonder at the possibilities. The northern continent might have had any of the names shown in the table here had Mr. Mercator had marginally better historical records. Just think, the melting pot of the world might have called itself the United States of Karlsefnia. There might have been a fabulous flower called the Brendanan Beauty Rose. A famous novel might have been written entitled "The Ugly Snorrian." And who knows, the early natives could have been Sinclairian Indians. Can you imagine singing "God Bless Bjarnia" or "Luckyleifia the Beautiful"?

Apart from all these dubious European commemoratives, there was one indigenous name that almost did take hold. The Aztecs referred to their own great civilization as Mexica and those syllables were adopted by the live-in Spaniards to label an expansive country reaching to the northern salt flats of what is today Utah. In fact, in the early 1600s, a London book of maps labeled the two western continents Mexicana and Peru. Justice and poetry would have been served, I believe, had that atlas been more popular and those names prevailed.

In any case, it does not matter because by the middle of the 17th century, on all the other maps being published in the old world, the new continent across the north Atlantic was indelibly labeled as North America.

From the beginning inhabitants on both sides of the Atlantic were referring to the settlements in the new world as "the colonies," and by the 18th century the British were calling their colonist cousins "Americans" and that land over there "America." (The Spaniards were calling their colonists Columbians.) So even though there was no sovereign country the people and their land were already labeled.

Inevitably the colonists began to feel the distance between themselves and the motherland. Though they had no notion of nationhood — not together anyway — they were concerned with provincial sovereignty. Then things began to change in the 1770s when tea and taxes turned into torrid topics. United action against England was gaining support, and by January of 1776, patriots like Thomas Paine were using the phrase "free and independent States of America." He was not talking about a new country, just an alliance of so-called sovereign entities he called "states."

By May of 1776, a resolution was adopted in Philadelphia exclaiming "that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States." The path was inevitable; the united colonies would fight England until they were free.

"I shall rejoice to hear the title of the United States of America," wrote a citizen in a letter to the Pennsylvania Evening Post on June 29, 1774. By the end of June, 1776, a number of people in Philadelphia were calling the union by those words. The name was sanctified when Thomas Jefferson penned that immortal phrase for the Second Continental Congress in "the unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America."

By the time war began with England, this mechanical and mundane designation was so much in use that on September 9, 1776, it gained official status when the Second Continental Congress authorized "that in all continental commissions and other instruments where heretofore the ‘United Colonies' have been used, the style be altered for the future, to the ‘United States'." When the Continental Congress of 1787 met to make that "league of states" into a true nation, only one name was on every pertinent document — the United States of America. Shades of "Dakota" — "many in one." At least the Indians could say it in one word.

Would not a name like Canada have been crisper and stronger than something that is not a lot different from "People's Republic of America"? Like "tra la la," the pleasant string of sounds "Canada" is a song. In 1535, Indian scouts led Jacques Cartier to the place "kanata," the Huron Indian word for village. In 1791, the word that had been applied to the territory north of the American colonies became official when the Province of Quebec was divided into the colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada. 1841 brought union and today the name is simply Canada.

"The United States of America." I suppose it could have been worse. They might have called the country New England, or as was later proposed Freedomia. But could they have done better? Was there some single word name that would have better suited this new and grand nation?

Let's imagine that we are delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and we insist to the others that the nation needs a regular name like the other countries have, such as France or Egypt. Ben Franklin agrees with us and suggests that we draw up a list of name candidates and to present our recommendations to the Congress. Now, imagine that we're sitting in the Man Full of Trouble Tavern, at one of those tables in the corner, and we scribble down some of our favorites, like...

Atlantis, Atlanta , Columbia, Freeland, ChrisCo, Democratia, Libertia, Liberia, Republica, Freedoma, Peoplonia, Utopia.

Okay, you've had a couple of beers and it is time to go — what's your favorite name for our country? I suggest we go back to the delegates with the recommendation that the nation call itself Liberia before the slaves run off to Africa with that name. (As it turns out, they never did seem to make it work for them.) My guess is the Congress will wrangle over the options and come to no consensus. Finally, Ben will suggest that for the present, with other pressing business before the Congress, we stick with "the United States of America." Who can argue with Ben?

So what do you call the residents of those united and prosperous states of the north Atlantic continent? "Americans" you say? Aren't their continental neighbors — those living in Canada, Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama — also Americans, as well as the people on the South American continent?

Yes, yes, I admit, "American" is cemented into the language forever. But let's face it, it's not fair to all the other inhabitants of the New World. And some of them resent it. They may, through habit or expedience, use the label "American" to refer to those Yankees or Gringos, but they prefer "Yankee" or "Gringo."

The Canadians don't care much because they like being called Canadians. But south of the border the arrogant Americans are formally known as norteaméricanos. In some places, they are called estadounidense which translates to United Statesians. It is a little long, but an accurate demonym, don't you think? Many norteamericano writers, such as H. L. Mencken and William Safire, have proposed other ways to refer to the estadounidense, including Amus, Mesoamericans, Staters, Statesmen, Usams, Usians, Ussies.

To me, they all sound a little too un-Bjarnian.

|

Other Pages in Names Galore | |

|

Famous Cowboy Names Sports Team Names Other Name Lists

|

Name Generators Naming Fun Stories about Names

|