The drizzle streaked diagonally in the cold wind as the coaches gestured frantically at their players. Yells and screams boiled out of the stands. The stadium lights glinted on puddles and shiny helmets and wet umbrellas. The Quakers of Eastern High had just fumbled the ball on their own 48 yard line. That was good news for the Holt High Rams who were down a field goal with less than a minute to play.

I pulled up the hood of my parka and shivered with an urgency, wondering if I should make a dash to the Port-A-Potty or let the wet night conceal an indecent relief. In that confounded moment of excitement and damp pain, Jim Johnson yelled over the noise into my ear, "We're starting a bowling team in the City League."

I tried to imagine how Jim could possibly be thinking about bowling at a time like this. Nothing came to mind as I just looked at him through the water beads on my glasses. As I turned back to the field to see the Ram quarterback bark out his signals, Jim shouted, "Want to join?"

"Sure, I like indoor sports," I replied licking the rain from my lips. "What's the team's name?"

"Name?" It was obvious he had not thought about it at all.

"Yeah, what are you calling our bowling team?" I asked watching the mucky Quakers pile on top of the soiled Ram halfback. As I squinted at the muddy melee, it dawned on me that the "Quakers vs. Rams" metaphor just didn't work. Would any real Quaker ever confront a ram, I thought.

"Team name? Do we need one?" Jim Johnson asked.

"Yes. You're not just going to refer to the group as "us guys,' are you?"

He rolled his shoulders and cocked his head. "Come to think of it, that's as good as anything else. The Us Guys."

"No, no," I said. "You can't pick the first name you hear. Let's think about it. There has to be a logic to the name. It should be something pertinent or emblematic. How about something like the Lucky Strikes, or the Spare Ribs?"

He shook his head, "Who says it has to be logical?" Then he mumbled to himself, testing the sound of it again, "Us Guys."

I offered more. "Or the Fighting Head Pins, or the Fighting Pin Heads?"

The clock showed twelve seconds and the Rams quarterback dropped back for a pass. Johnson was shouting, "Go Us Guys! Go Us Guys!" The quarterback dodged a red dog and threw up a "hail mary" in the end zone. We all stood up and yelled. The wide receiver made a leaping catch and then did a Heisman pose while Johnson yelled "Us Guys score! Us Guys win in an upset!"

Time ran out, and I had just become an Us Guy.

– Ω –

[ Go to end ]

At that game, at that moment, I realized that Johnson was right. Names do not have to be logical — and, in fact, they rarely are. One can think of few aspects of life where the creation of names is a consistent and orderly process. Sure, cities have tried to be systematic in naming their streets, astronomers in coding the stars, biologists when they classify the plants and animals, and drug companies when they christen their chemical compounds. But exceptions always arise and before long the schema of names is as orderly as trail mix.

On the other hand, one might suppose that, in sports, where rules are paramount, team monikers would be assigned systematically and logically, that they would follow a motif or have a consistency across the league or conference, or denote some profound or prominent aspect of each team. Yet, in this most regulated arena of human activity, where even the clothes are called uniforms, naming has fewer rules than a street fight.

Lions vs. Dolphins in American football [touch]

Everywhere, nicknames of sports teams can be anything — birds, barbarians, clans, colors, mammals, myths, pets, plants… you name it. We have Lions sparring with Dolphins, Bulls battling Pistons, Boilermakers competing with Buckeyes, Indians up against Blue Jays, and Penguins vs Maple Leafs (by the way, shouldn't they be Maple Leaves?). None of it makes sense — not even poetic sense.

And if you think such naming anarchy is the cost paid for picking an apt name for each team, explain the Wolverines of Michigan where no such animal lives, and the Lakers of Los Angeles where there are no lakes. Such irrelevance is not just an American inclination. Consider the Flames of Calgary in Canada, or even the Aztecs of Bristol in England. In short, there are no rules in the naming of sports teams.

How did this nicknaming heritage come about? As usual, the answer is rooted in history — not just recent sports history — but way back to the Templar knights or the Black Friars of the 12th century. In the early United States, the tradition of naming testosteronic groups continued with the Jersey Blues militia, Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys of Vermont, the Jayhawkers in early Kansas, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders and Pershing's Doughboys (not exactly a name to strike fear in heart of the enemy, eh?)

The practice blossomed in early 19th century America when sports clubs began sprouting up in the eastern cities. By and by, they became formal organizations and dignified the notion that men could play and not feel guilty about it. These fellowships generally took stiff and formal names like the Washington Base Ball Club, but after a time they adopted more spirited designations like the Eagles of New York, and the Olympics of Philadelphia. And who could forget the Brooklyn Bridegrooms? Apparently everyone.

Probably the oldest name in modern organized sports sprouted like a mushroom, not because someone planted and harvested it, but because the climate was right. In the 1830s, there was a men's association called the New York Base Ball Club. It included merchants, lawyers, bank clerks, and others who were free after three in the afternoon to play a new sort of game, an amalgamation of "town ball" and "rounders." The games were informal with seldom any onlookers or fans shouting "kill the ump."

Then in September of 1845, some of the younger members of that club got together and formed the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. Using the field at Madison Square, they adopted formal rules and by the 1850s, they were inviting the Washington Gothams to play their game. Thus the "Knicks," as they were called after a time, ushered the game of baseball into America's pastime. Today that first team nickname lives on with the New York Knicks basketball team.

But why did these early nineteenth century gentlemen choose the lanky name of Knickerbockers? Where did the word come from? Possibly it referred to the loose knee-breeches, worn by boys, cyclists, old time golfers and ball players. But where did the garment get that name?

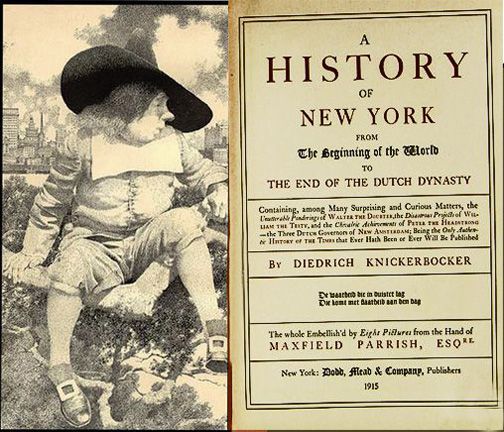

In all probability from George Cruikshank's illustrations in Washington Irving's book, History of New York. In it, he drew the Dutch settlers of old New York, then called New Amsterdam, with breeches cut and crimped at the knees. This satirical book was published in 1809, not under Irving's name, but under the pen name Diedrich Knickerbocker. Soon columnists began to refer to New Yorkers as "Knickerbockers" and the moniker stuck.

But the origin goes deeper because Washington Irving had a reason in choosing that pseudonym as the author of his book. Although the name is rare in the Netherlands today, it became an American surname when Harmen Jansen Knickerbocker came from Holland to settled in New Amsterdam in about 1674. His family prospered there as did those of many newcomers of that era, and that proud and noble name of Knickerbocker came to symbolize their blue-blooded colonial lineage. The really interesting thing about this extinct Dutch name is that it originally meant "clay baker" or simply "potter." So, essentially, when you get down to the heart of the matter, the New York Knicks could be known as the New York Pots.

The Knickerbockers and their new game were just the start of something really big. With the industrial revolution and automation squeezing a large amount of labor hours out of the economy, it was only natural that the birth and growth of professional sports would absorb a good portion of that "free time." And, like Jim Johnson's bowling team, all the teams in all the sports that blossomed in the 19th and 20th century had to be called something.

Professional baseball has led the parade of sports into the American culture and with it the pageant of peculiar nicknames. In recent years, expansion of the two baseball major leagues has brought an influx of new teams. But as we can see in the table Major League Baseball Team Names, there has always been a churning of identities.

Take, for example, Boston's professional baseball teams. In the National League, the Beaneaters have been known by eight nicknames, and in the American League by six. They include rocks, clothing, birds, insects, and all sorts of people. The litter of icons looks like the contents of some minor god's junk drawer.

Yes, there are a few apt names. The moniker Brewers reflects the traditions of Milwaukee. Twins alludes to the neighboring cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Rockies is a fitting icon for any Colorado team as is Orioles for Baltimore. There are even some clever names in the minor leagues, like the Bats of Greensboro (now the Grasshoppers), the Sounds of Nashville, and the Lookouts of Chattanooga. But such scant poetry as these makes even the inconsistency inconsistent.

Advertisement

It's not just the scrambled imagery that results from such an unstructured system. There are other problems. Too many teams share the same nickname.

For example, back in the 1997 NCAA men's college basketball tournament, the final game of the contest found the underdog University of Arizona facing the favored University of Kentucky. On Monday night, March 31, the teams fought to a tie in regulation play and with great drama the game went into overtime. When it was all over the final score was the Wildcats 84 and the Wildcats 79.

The anarchy in team names means that silly is acceptable too. In 1996, the capital city of Michigan won a minor league baseball franchise and had the opportunity of coming up with a new team name. As so often happens, a contest was held and hundreds of people submitted entries, many with an automotive theme because the city's economy was dominated by automotive assembly plants. The apt icon Pistons was already in use in nearby Detroit; but there were other glorious possibilities to pay tribute to the car: Roadsters, Spark Plugs, Wheels, Turbos, Rally, and many more.

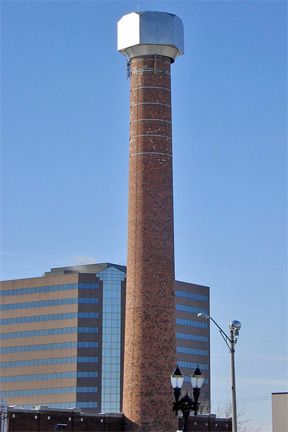

Some people joked that they would end up calling the team the Lansing Oilpans, or the Dip Sticks, or the Lugnuts. But seriously… the winner was… Lugnuts!...? The hope and honor of local sports fans turned to sighs and silliness. Some loved it, others hated it. Many laughed at it, a few with it. To top it off, a gigantic replica of a stainless steel nut was placed atop a downtown smokestack that pretended to be a lug.

Sometimes the nickname is merely a trivial consequence of obscure events. For example, in Green Bay, Wisconsin, one August day of 1919, Earl "Curly" Lambeau and George "the Gipper" Gipp decided to create a football team and so recruited employees of the Indian Packing Company. It seemed only natural that they would be called the Indians, after the company. But even back then, some people were sticklers for political correctness even without knowing what it was. They objected to the "racist" moniker. It didn't matter that the Cleveland baseball team was using the same nickname without rancor or that Lambeau's alma mater was known as the "Fighting Irish."

The red flag had been raised; so a new handle had to be selected. (The company was bought out by the Acme Packing Company in 1921, so the rationale for the reference to the native Americans was lost.) A sports writer was referring to the team as the "Big Bay Blues" in his columns but it would not stick. Instead, the colloquial and uninspired "Packers" was being bandied about enough to forge a consensus, and it became official. So the town went from spotlighting the native Americans to limelighting the meat workers — from "racism" to "occupationism." Perhaps they should have followed the company's lead and become the Green Bay Acmes.

The sports past is strewn with curious names from curious places. In the early years of professional football, there were the Duluth Kellys (1923-25), the Detroit Heralds (1920-21), the Minneapolis Marines (1922-24), and the Rochester Jeffersons (1920-25). For a complete list, check out the Professional Football Team Names table. Ever hear of the Pottsville Maroons? These coal crackers from a small town in Pennsylvania were the hottest pro football team in 1925. The Chicago Bears originated from a team called the Chicago Staleys, named after a sponsoring starch company in 1921.

If you try to trace the history of some of these team monikers, it can get rather confusing. For example, Cleveland has had several unrelated teams playing in the city. Back in the 1920s, the Cleveland Tigers joined the new NationalFootball League, then became the Indians. But a different Indian team started up in 1923 to become the Bulldogs. Later, a Cleveland Rams team joined the NFL in 1937. But when in 1946 the Rams moved to Los Angeles (and eventually in 1995 to St. Louis whose Cardinals (which came from Chicago in 1920) went to Arizona in 1988, and then returned to Los Angeles in 2016), a new team was created and Paul Brown was named general manager and coach.

A contest was held to pick a new nickname. Panthers was the favorite, but it was already taken by another Cleveland team. So instead, as a tribute to the new coach, the owners called the team the Browns. I still find it baffling that this truly prosaic surname based upon a dull color would become the rallying syllable for a football team. I cannot help but wonder if the coach's mother had married someone else, would they have become the Cleveland Shapiros? The Cleveland Crenshaws? Or possibly my favorite, the Cleveland Johnsons?

Paul Brown was fired in 1963; so he went to Cincinnati. There in 1970, he organized a new football team that would join the National Football League in its expansion. Since he had left his name in Cleveland, he had to come up with a new team handle. What he chose, without checking the dictionary, was a reference to a region of the Indian subcontinent in the northeast around the vast Ganges and Brahmaputra deltas which is now divided between India and Bangladesh and known as Bengal... so the team became the Cincinnati Bengals. Paul Brown might just as well have called the team the Cincinnati Canadas, or the Cincinnati Baltimores because technically, in spite of what he may have thought, Bengal is no more a tiger than Canada is a goose or Baltimore is an oriole.

Alas, Cleveland football fans were abandoned once more in 1995 when owner Art Modell moved the Browns franchise to Baltimore to become the Ravens. Angry Cleveland fans put up such a stink that they eventually got a new team for the 1999 season. What did they name it? Incredibly the diehards insisted on that old somber syllable, that drab word with no allegoric significance, that simple sound with lots of local soul — the Browns. Now that is red-blooded loyalty.

Modell had taken his Ravens to Baltimore because their Colts went to Indianapolis in 1984. The Colts had come to Baltimore in 1953 when the Dallas Texans went belly up that year. In 1960, Dallas got a new NFL team, the Cowboys. At the same time, in the American Football League, Dallas had a new team of Texans, but they moved in 1963 to Kansas City to become the Chiefs. In 2002, a new Texan team arrived, this time in Houston because in 1997 their Oilers went to Memphis to become the Titans. One wonders if you are suppose to root for the players, the franchise, the nickname, or the city.

Even if there is no league-wide rationale for team names, it is refreshing when a team takes an icon that depicts some characteristic of its locale, as with the 49ers, a memorial to the pioneers that shaped San Francisco's early history; or the Patriots, a reflection on colonial New England; or the Steelers, a tribute to Pittsburgh's laborers in the steel mills. Giving such relevant names to sports teams might be the only cerebral aspect in that corner of our culture where, to quote Charlie Brown, winning isn't everything but losing isn't anything.

What are Buffalo Bills

[touch]

But a socially or culturally relevant nickname often gets passed up for an easy play on words — like the Buffalo Bills of the National Football League. Yes, there was a famous cowboy known as Buffalo Bill, one William Frederick Cody born in LeClaire, Iowa in 1846. But as far as I can find, he never set foot in that town by the lake. Oddly enough, in the 1920s, Buffalo had a football team known as the All-Americans who became the Bisons in 1945. But that incorrectly pluralized noun (bison, like deer, is also plural without an s) was already being used by their baseball team. So for identity's sake the team held a contest in 1947 and the winning name was Bills. The owners could have opted for Buffalo Bullets or Buffalo Nickels from the entries, or even gone for Buffalo Buffalos. But instead, they preferred a team name that basically means "beaks of bison" (cursor over or touch the image at left.)

A more relevant play on words once adorned the baseball standings in the early 1960s when the town the Spaniards called "City of Angels" became the home to the Angels. But the poetry was lost in 1965 when owner Gene Autry moved his team to neighboring Anaheim with the name California Angels. Then in 1997, when The Walt Disney Company had controlling interest, a new contract with the city of Anaheim stipulated that the city's name be part of the team moniker. Hence the broken allusion gave way to alliteration and the team became the Anaheim Angels. Then, in 2004, with much rancor and multiple legal challenges, the franchise became the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim. In 2016 the team became simply Angels. Ah, those wings do work.

A minor league baseball team in western Michigan represented two cities — Kalamazoo and nearby Battle Creek. Originally, the fans were threatened with a team name of the Golden Kazoos even though neither city has any connection to this annoying instrument, or the color for that matter. Imagining the inevitable rallying sound of grandstand kazoos, the fans protested, saving them from that fate. In the end, the team became the Battle Cats, a linguistically apt moniker for one partner city, but not the other. I wonder if they considered the Battling Kazoos? Doesn't matter — they eventually became the Battle Creek Yankees, and then in 2007, moved to Midland as the Great Lake Loons.

The pros are not alone in this chaotic name game. The thousands of high schools, colleges, universities, and weedy leagues offer a menagerie of marks and mascots. I culled through a list of college team nicknames in the United States and found there were over 400 distinct nicknames being shared by one or more of the more than 1500 institutions. Disregarding the leading adjectives (like Fighting, Big, Golden, etc.), only about 17% of the institutions have unique nicknames, like Cornhuskers, Spiders, Salukis, Hokies, and Rosemonsters. For a complete list of the most popular nicknames and their frequency, check out College Team Names.

The variety is astonishing. There are Poets and Warriors, Bees and Whales, Demons and Angels, Wildcats and Bulldogs, Thunder and Lightning. The teams come in a rainbow of colors like the Golden Flash, Green Terror, Crimson Tide, Blue Knights, Black Flies and, of course, the Rainbow Warriors. Some are caught in the most peculiar activities, such as the Praying Colonels, the Running Rifles, the Ramblin Rams, the Hustlin' Owls, and the Flying Dutchmen. How about the Battling Bishops of Ohio Wesleyan University — I'll bet they are a holy terror.

Some nicknames are a little more thoughtful, like the Paladins of Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. A paladin is, among other things, a trusted military leader, a word arising in the time of Charlemagne. Then there are the Stormy Petrels of Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, Georgia, a name coming from the sea bird thought to walk on water, also known as St. Peter's bird.

It is patently clear from the collegiate list that animals of all kind are the favorite mascots, accounting for over half the nicknames, everything from Anteaters to Wolverines, Gators to Gophers. The mascot of choice is of course that national symbol of the United States, the eagle, chosen by more than 72 American institutions of higher education. Among them we find twenty-one different kinds of Eagles, like Runnin' Eagles, Marauding Eagles, Screaming Eagles, as well as eagles in all sorts of colors, mostly Golden Eagles. Alas, there is only one Bald Eagles (Lock Haven University of Pennsylvania), and in spite of the virile sound of it, no Balled Eagles.

The most favored animal genre for collegiate team nicknamers is the cat family. It's a jungle out there with everything from the concocted AMCats of Anna Maria College of Massachusetts to the ever prevalent Tigers, favored by 48 institutions.

This list of team cat names shows the popularity of feline mascots. It's a little odd that this affection for felines should result in so much duplication when there are so many other fine large cat varieties with no representation — like caracal, cheetah, kodkod, manul, margay, serval, and oncilla. However it's not surprising no team calls themselves the Pussycats.

|

College Teams | |

| Tigers | 48 |

| Lions | 43 |

| Panthers | 36 |

| Wildcats | 34 |

| Cougars | 28 |

| Bobcats | 19 |

| Bearcats | 11 |

| Jaguars | 6 |

| Bengals | 3 |

| Leopards | 3 |

| Lynx | 3 |

| Catamount | 2 |

| Mountain Lions | 2 |

| AMCats | 1 |

| Bearkats | 1 |

| (Lady) Cats | 1 |

| Hillcats | 1 |

| Mountain Cats | 1 |

| Ocelots | 1 |

| Pumas | 1 |

| Sabrecats | 1 |

| Tomcats | 1 |

| Total, all cats | 244 |

Although there are no house cats roaming college campuses as mascots in the U.S. (only the Tomcats of Thiel College), there are teams named for several dog breeds, including Huskies, Bulldogs, Bloodhounds, Greyhounds, Pointers, Retrievers, and Terriers. Clearly big dogs, like big cats, make great team mascots, even if they are not as ferocious. Apparently it's the bark, not the bite, that counts. (If you want to investigate the variety of college nickname yourself, see College Team Names.)

Most large mammals make good mascots because they can be paraded with majesty on the sidelines of stadiums and arenas (or is it stadia and arenae?). But small reptiles and insects present a challenge. There are the Texas Christian University Horned Frogs, the St. Ambrose University Bees in Iowa, the University of Richmond Spiders in Virginia, and Boll Weevils of the University of Arkansas at Monticello. These icons require the amplifying aids of wire frames and paper mache. And teams with nicknames of earthly and heavenly phenomenon, like the Storm of Lake Erie College in Ohio, the Comets of Olivet College in Michigan, the Hurricanes of the University of Miami in Florida, and the Stars of Oklahoma City University, must resort to costume personifications. Equally challenging are intangible icons, like the Northern Lights of Montana State University-Northern, the Beacons of University of Massachusetts-Boston, the Express of Wells College in New York, and the Pride of Greensboro College in North Carolina. But then these teams don't have to worry about the care and feeding of their mascot.

The stories behind most of the college mascots and marks are not particularly noteworthy. Not even for some of the oddities, such as the athletes at Washburn University who are called the Ichabods simply because that was the first name of an early benefactor who gave his last name to that institution. The origins of the Jimmies of Jamestown College, the Tommies of the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, and the Bonnies of St. Bonaventure University are all obvious. A few of the college nicknames, however, are curious enough to entertain those who like to wallow in such trivia.

For example, one of the more cryptic college nicknames dates back to the Civil War. In a battle in Virginia, a regiment of North Carolina confederates was passing a retreating regiment when one of the beaten regulars asked the Carolinians mockingly, "Any more tar in the Old North State, boys?" This was an unkind reference to the fact that the State was known for its tar, pitch and turpentine, all extracted from Carolina's vast pine forests for use by the British Navy back in colonial days. A Carolinian replied, "No; not a bit; old Jeff's (referring to Jefferson Davis) bought it all up. He is going to put it on you'ns heels to make you stick better in the next fight." Upon hearing of the exchange, General Robert E. Lee is purported to have said, "God bless the Tar Heel boys." That odd appellation became synonymous with bravery and then later a troop of athletes from the University of North Carolina.

In the first decade of the 20th century, an elfin figure with rounded belly, pointed ears and mischievous smile became the rage across the country. The Billiken Company of Chicago bought the rights to the impish character and produced toy banks, statuettes and all sorts of objects based upon it. The figure in any incarnation became known as a "billiken." At about the same time, it was noticed that the football coach for Saint Louis University, John Bender, had a similar physique. The joke spread to include the athletes, and by 1911 the team was know as Bender's Billikens. Over time they became just the Billikens.

Originally, the Michigan Agricultural College teams were known as the Aggies along with those of eight other institutions at the time, not because the students were marble heads, but because their school was an agricultural college. When it became Michigan State College in 1925, a new nickname was needed to escape the bib-overalls image. In the best tradition of selecting a new name, a local contest was held. The winning entry was the sober and utterly unique moniker, "Michigan Staters." One individual who didn't like it was a sports writer who selected his own favorite entry from the lot. So by the power of the press, the team became the Spartans, joining fourteen other teams in the nation with that nickname. I wonder if the Fighting Farmers was a candidate.

When the University of California began the Santa Cruz campus in the 1960s, the students had adopted a humorous interest in the banana slug, a slimy gastropod found in the coastal redwood forest. They named their newsletter after it and before long a few minor sports teams on campus took the nickname. By the 1970s, the student body became quite attached to the slimly little creature. So in 1981, when the campus administrator proclaimed with well-intended sanity that the school's mascot was officially to be the Sea Lion, students rebelled. They continued to root for the "slugs" even after a sea lion was painted in the middle of the basketball floor. In 1986, the student body voted in a straw poll by a margin of 15 to 1 in favor of the mollusk over the mammal. The furor attracted nationwide media attention. The administration finally gave in and Banana Slug became the official mascot. In 1992, the National Directory of College Athletics named the Banana Slug the nation's top mascot edging out the Stormy Petrels of Oglethorpe University. That same year, Sports Illustrated Magazine named the slug the nation's "best college nickname." You might say it was a happy ending to a real slugfest.

One cold April day in 1904, the Pennsylvania State College baseball team arrived at Princeton University to play the Tigers. Before the game, on a tour of the campus, the Pennsylvania players were proudly shown a beautiful sculpture of the Princeton mascot, a Bengal tiger. The tour guide alluded to how ferocious the animal was. The third baseman of the team with no nickname quickly rebutted the boast with "Well, up at Penn State we have Mount Nittany right on our campus, where the Nittany mountain lion rules and has never been beaten in a fair fight. So Princeton Tigers, look out." No matter that there was no such lion roaming Nittany Mountain — the peak named after legendary Indian Princess, Nita-nee — a mascot and nickname had been born.

Advertisement

Nittany Lions, like regular lions, comets, bears and pioneers, are not necessarily males, not like Bulls, Cowboys, or Gamecocks. But apparently the Penn State University female hoopsters thought so. They chose to be called Lady Lions. The women athletes at Southeastern Louisiana University, Missouri Southern State College and Mars Hill College are also Lady Lions. East Carolina College has Lady Pirates, Johnson C. Smith University has Lady Bulls, and University of Tennessee has the Lady Volunteers. Several women's colleges did not have to ladyize the team nicknames, like the Belles of Bennett College in North Carolina, the Katies of St. Catherine College in Minnesota, and the Jennies of Central Missouri State University.

This gendering trend continues at coeducational institutions around the country — even at the high school level. In Illinois, of the approximately 700 secondary schools in that state, about forty percent have different monikers for the girls' teams. However, ninety percent of these simply added the word "lady" to the boys' team nickname, so that we find Lady Panthers, Lady Hawks, Lady Grey Ghosts, etc. In some instances, the result is a little strange as with Lady Knights, Lady Dukes, Lady Minutemen, and Lady Cavaliers. There are even Lady Missiles and Lady Suns, whatever those are.

Lady Hawks, Lady Panthers? If it was necessary for some distinction reasons, why was it the girls' team that added a word? Why not Gentlemen Hawks or Gentlemen Panthers? Other questions come to mind. Why was "lady" — a word viewed by some as sexist — an overwhelming favored modifier? Why not She Lions or Women Patriots? And what are we to make of the oxymoron Lady Warriors? (Perhaps they only fight in "civil" wars.)

|

Some High School | |

Boys Teams Bearcats Blueboys Braves Broncos Cougars Cyclones Dukes Eagles Flyers Golden Eagles Hilltoppers Hornets Mightymen Minutemen Mustangs Orphans Pilots Pirates Princes Raiders Rajahs Rangers Rebels Steelmen Tars Tigers Warriors Wolves | Girls Teams Cats Bluegirls Bravettes Fillies Cougarettes Blazers Duchesses Eaglettes Flyerettes Golden Girls Angels Hornettes Mightywomen Minutemaids Fillies Orphan Annies Co-pilots First Mates Princess Raiderettes Rajene Rangerettes Belles Steelwomen Tarettes Tigerettes Warriorettes Wolfgals |

There were some schools that bypassed the "lady" gimmick in distinguishing the girls' team from the boys', as shown in the table to the right. A few sought equality with such nicknames as Mightywomen, Steelwomen, and Wolfgals. Yet some simply took a diminutive spinoff of the boys' nicknames, such as the Bravettes, Fillies, and Minutemaids. Even more unbelievable in this day and age are the girl Co-pilots vis-à-vis boy Pilots, or the girl First Mates who are classmates of the boy Pirates. In only two instances did the female team show complete independence from the male team; in one case the girls chose to be Angels instead of Hilltopperettes and in the other they became Blazers instead of Lady Cyclones.

It is all very curious. But I guess like all the other revolutions caused by the dominance of one group over another, the need to make women's sports more visible has brought about an overreaction. So when the men's team is named one thing, like the Owls, the women's is often compelled to choose something else, like Lady Owls, or Owlettes or Hooters, or whatever.

Speaking of political correctness, at the turn of this century, there arose a taboo against team nicknames that refer to the people who wandered onto this continent from the west before the Europeans landed here in the east. By 2002, over 600 of the roughly 3000 sports teams with Indian related nicknames had adopted new mascots. The uproar was not only about using the tribe names like Chippewa, Huron and Mohawks, but also references to their culture such as Chiefs and Braves, as well as any reference to the race itself such as Indians, Reds, and Injuns.

The claim was that the names belong to the tribes for their use only, and that mascots and gimmicks such as tomahawks and feathers only perpetuate an image of savagery and cultural backwardness. Indian leaders contend our society would not stand for the naming of a team, for example, as the Denver Darkies, the Kentucky White Trash, or the Jersey Japs. The board of Miami University in Ohio apparently agreed with this notion when it voted in 1997 to change the school's designation from Redskins to Red Hawks. I suppose Redskins is a little tainted by the past, but still a team ought to be able to be named after a potato. Turns out the Washington football team shed that same team name in 2021 for a temporary soccer-like name, Washington Football Team. In 2022, they became the Commanders.

Redskins football team

[touch]

The political correctness of this whole notion is not all that clear, however, since the roster of college team names does include all sorts of clan designations including Swedes, Quakers, Scotties, Dutchmen, Irish, Celts, and Ragin' Cajuns. In all cases these second-hand owners of these monikers all seem to be dedicated, proud and conscientious athletes even though unflattering caricatures of those namesakes perform silly antics on the sidelines.

The premier example of this issue was found with Cleveland's baseball team. I'm not exactly sure who was right, those for or against the name "Indians." Both had compelling arguments for their views. American native sympathizers resent the fact that the colonial civilization (either the United States or Cleveland, I am not sure which) is capitalizing on the old native culture without its permission — kind of like dressing up as Elvis without Priscilla's permission and making money at it.

On the other hand, loyal sports fans in the city by the lake contended that the name Indians was given respectfully. It began in 1897, they say, when Louis Sockalexis, a Penobscot Indian from Old Town, Maine, joined the Spiders of Cleveland to become the first American Indian to play major league baseball. In his first game, he homered his first two times at bat. During that season he was hitting over .400 and Cleveland was being called the "Indian's team." However, Sockalexis' career quickly went downhill because of injuries and other bodily abuses. By 1902, the Spiders became the Blues because of the color of their uniforms, then the Broncos, and then the Naps, nicknamed after the Napoléon Lajoie who was a well-liked player-manager at the time. When Nap was traded away in 1915, a contest was held for a new nickname. The winning entry offered the moniker Indians in honor of the former great Spiders player, Lou Sockalexis.

However, the Indian protagonists were not buying that historical account as a valid rationale. They thought it made as much sense as saying the Giants were named after their first catcher who was very tall. And just look at that old Cleveland logo, they said; it sported a revolting caricature called Chief Wahoo, a big-nosed bozo with a feather in his head. To appease these more native Americans, perhaps the owners of the Cleveland Indians should have nixed the feather and dressed him in a Nehru jacket and called the caracter Sahib Wahoo. But alas, Wahoo was gone, replaced by the letter C. Finally in 2022 the team dropped the Indian altogether and took a new name, the Guardians, a reference to city's Hope Memorial bridge called the "Guardians of Traffic". Yet wouldn't something related to the lake to its north, like the Lakers, be more appropriate? Yes, I know, it's the Los Angeles basketball team name. But screw them, they're not even on a lake.

Some teams are accused of insensitivity even when they may be innocent. Take the Redmen of St. Johns University in New York, for example. That team at first resisted the call for change because it insisted that the designation derived legitimately from the color of the players' jerseys. Maybe — but then why not Redshirts or Scarletmen instead? They yielded to the pressure and ended up the Red Storm, whatever that is. The Redmen of the Carthage College in Wisconsin finessed the issue by becoming the Red Men — and wouldn't you know, the women are known as Lady Reds.

When a team does bow to political correctness to give up its allusion to native culture, you might think that it would select a really clever new nickname, one that is pertinent or poignant or profound. Yet, in 1992, when the Eastern Michigan University Hurons took the "pc" step, they chose to become the Eagles, joining the flock of 78 other universities in the United States so called. Likewise, over in Milwaukee the former Warriors of Marquette University became the Golden Eagles just like 13 other institutions sporting those auric feathers. In both cases, I guess they gave more thought to what they did not want to be called than what they did.

There was one team, though, that was entitled to be called Indians. In 1922, Walter Lingo, owner of the Oorang Dog Kennel in LaRue, Ohio organized a professional football team to travel around the country and advertise his business. Before the game and at half time, there would be exhibitions showing off Lingo's dogs. The Oorang Indians were not very good but they were truly American Indians including Olympic star Jim Thorpe and other natives with names like Long Time Sleep, Joe Little Twig, Big Bear and War Eagle. The team folded its teepee after two years.

This anthology could go on, but it should be obvious by now that it's all a big game, naming teams after animals and objects, clans and creatures, bellwethers and benefactors; a game motivated by whim and romance, fad and fancy, and sometimes just plain silliness. It's a game that every team played at least once in some local and short-lived fanfare. Any number can play, from one sportswriter to a thousand fans. It is a game with no rules.

So what, you say. Well, let me suggest what is wrong with this name game. Since sports are coordinated activities directed at objective goals following absolute rules, it would be interesting at some intellectual level if the contests made some attempt to pose as allegories to real battles in the real world. For example, Pirates vs. Mariners, Cowboys vs. Indians, David vs. Goliath, Sun vs. Rain, Wellington vs. Napoleon. But alas, no — what we have are fractured allegories like Tigers vs. Rockies, Orioles vs. Indians, Red Wings vs. Maple Leafs.

When two teams meet, headlines of that contest often play along with the suggested metaphor, if there is one, like "Tigers Maul …" or "Giants Stomp …" Unfortunately these headlines and stories are usually half-witted because look who the Giants stomped, the Rockies. What is the imagery in describing a basketball game between the Atlanta Hawks and the Miami Heat? Is it a large bird being chased by a flaming basketball? How do you visualize the mascots in a contest between the Vikings and the Jets? Is it Eric the Red thrusting a lance into the side of a Boeing 747? And what in the world is the allegory for a game between the Jazz and the Magic?

I think we need to get back to basic sports values where rules are the rule and team names make visual sense with realistic mascots. Even more, I think team names need to be coordinated within each sport and each league. Perhaps we need a federal law that mandates each sport to adopt a theme for its team names.

For example, football teams would have to be named after a class of people, like Pirates, Knights, Accountants, or Urologists, while baseball teams would use animals, like Lions, Beavers, Chipmunks, or Hippopotami, and hockey would take celestial things, such as Comets, Suns, Moonlets, or Cepheids, and basketball would follow fruits and vegetables.

Each league or division of a sport would use a subclass of the theme; so, for example in baseball's zoology, the teams of the National League would be named for marine creatures, such as Dolphins, Sharks, Tuna, Salmon, and Octopi and the American League would use birds like Eagles, Hawks, Sandwich Terns, and the Tropical Boobies.

Just imagine how informative such nicknames would be as you check out the sports news and read the headline, "Apples Get Cored" or "Carrots Are Shredded." Clearly we are talking basketball here.

Also see:

Professional Baseball Leagues and Teams

Historical Major League Standings

Professional Football Teams

Historical NFL Football Standings

|

Other Pages in Names Galore | |

|

Famous Cowboy Names Sports Team Names Other Name Lists

|

Name Generators Naming Fun Stories about Names

|